Vivian Lewin, Colville Suite for Mixed Voices

Lewin is deft in not only her curation of Colville’s artworks, but in responding to them in verse that is as observational and deliberately meek as the paintings themselves.

I am reviewing this book by looking at the Colvilles first.

Vivian Lewin is a Montrealer transplant from the US who studied English at Oberlin, taught quilting, and worked in communications. She is also a licensed Anglican Lay Reader and spiritual director, which I think is neat, and has published poems in Ariel, Fiddlehead, Field, and Matrix, among others.

This book came out with rob mclennan’s above/ground press in 2021. Each poem uses an Alex Colville painting as a reference point.

These paintings are so well-known, it is sometimes uncanny to look at them in the context of writing a review and realize I will be writing about a poem.

These are the ones I picked:

The opening and closing poem reference this painting. Due to formatting and time constraints combined, I will skip printing out the first poem as I usually do and merely comment on the vibe set by the opener of the chap.

We are greeted in this poem by quatrains, spaced out on all but the first line to the right, while the poem is aligned left, sort of resembling the seating arrangement of the perspective of the viewer of the painting and its subject.

Vivian Lewin comments: “the woman holding binoculars up to her eyes / and propping her elbows / on a wood bench as if she intends to watch forever – // carries the poignancy of transitory meetings / far from home, at airports / or the courthouse cafeteria / where we outdistance // the push and pull of our lives. [...]”

This is, of course, the famous Rhoda Colville, who was herself a talented artist and poet, as well as the frequent model (when it wasn’t a dog or a blind man) of Alex’s paintings.

Lewin returns to the painting in her closing poem, as well:

“[...] I stare at the reproduction / until I see only / geometry again, perishing / imperfect colours, // less certain than ever (and also now my back hurts). / It’s no different than / what we all do to one another. / So ordinary // that even if you went and stood so close your / eyelashes almost touched / the surface of the original / you might not be sure.”

This painting Lewin helpfully curates by including an epigraph from Alex himself underneath the title, which reads: “...there is no limbo, purgatory, / or hell for animals.”

In such delicate ways, each Lewin and Colville obscure the holy man with the pagan beast, if I can take such a liberty to compare them comically. Colville is taken very seriously and I don’t intend to crack wise here, either. But as someone with family members who, in the past, were involved with the holy life and one who was a trainer of hunting dogs, and hunter, you do get to form a relationship with canine that is simultaneously holier and more grounded than one might form with any so-called god, you know? That is very much what Colville’s painting speaks to me on, while taking Lewin’s perspective in good faith as someone involved with Christianity herself as she is.

This painting, Dog and Bridge, has been described elsewhere as demonstrating a “subtle profundity,” and I think that very much applies to both the human and canine scenes common to his imagery.

Lewin, in her sixth poem of the collection, references the above work and its associated studies. Colville spent years preparing for its execution on canvas. To quote the source linked in the paragraph just above:

The drawing Seeing-Eye Dog, Man and Bridge and its preparatory study (both 1968) were made nearly a decade before the large painting Dog and Bridge (1976). This chronology tells us important things about the later image. First, Colville had been ruminating on this theme and site for all this time. It is the same bridge, the same dog. Yet the drawings were not literally preparatory studies for the painting but rather parts of Colville’s characteristically long, and in all senses measured, thinking process.

Lewin is deft in not only her curation of Colville’s artworks, but in responding to them in verse that is as observational and deliberately meek as the paintings themselves. She embodies a transference of the visual medium to the verbal medium with poise and savoir-faire. There is no way to subtly put it, her choices and versification are breathtakingly spiritual and resonatingly sparing. She at once plays curator and visitor in a way that intimates such a familarity with the subject yet ushers you in at the same time.

This is some highbrow stuff, respectfully.

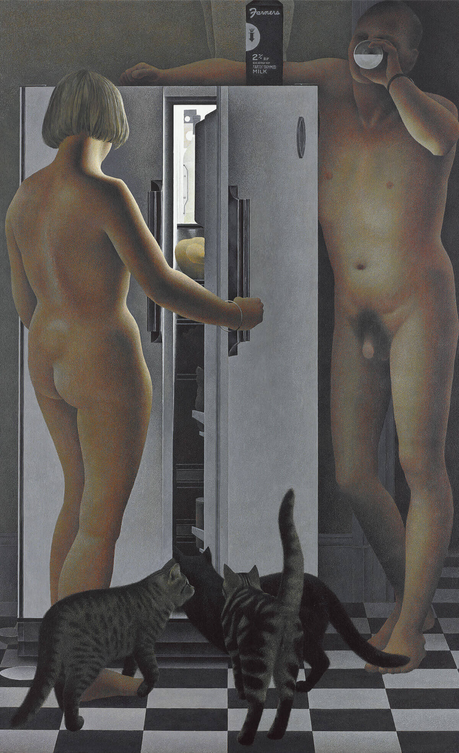

For the final painting above, she writes:

7. Colville’s Night Kitchen

Our eyes, getting used to the dark,

pick out a milky half-moon on the right

and lower, a man’s most private parts

not entirely in shadow.

Here’s life together, when it’s not

closed away altogether from what we see.

His refrigerator opens a gash of light

right down the middle,

revealing the man and woman of the house

wearing the slightly heavy limbs

of statues of gods whose skin

contains all colours

as they descend, spilling cold light

on black and white linoleum

and on three cats with tails that twitch

and noses that smell the milk.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.