Simon Peter Eggertsen, Hawking Comes Close to Finding God

It’s rare to witness the emergence of a writer such as Eggertsen in any time period, in any country, in any lifetime.

I open this slender volume at half an hour to midnight in the middle of the workweek. The lights all throughout the apartment are dim, the unseasonably foggy rain outside has trailed off, and the night is unseasonably quiet for Montreal. Winter has taken its toll on us. Just two weeks ago, a dump of snow we hadn’t seen the likes of in about 80 years. [Editor’s note: I am revising the draft of this review a month later, in April, and it is once again snowing.]

Now, as I delve into Eggertsen’s chap, burning the midnight oil, all my memories of teen angst, theoretical physics and atheism come flooding back.

An introductory word, the poet begins. He mentions A Brief History of Time, a book I first read when I was very precocious and successful in public school physics, then read again after I entered university. If I recall correctly, I first read it in the Kingston Public Library downtown at Bagot and Johnson. Then, I read it again after receiving it as a gift from my father, who acquired it at Wayfarer, with Walter’s unmistakable scrawl listing the price in pencil in the top right-hand corner of the flyleaf, $7 or $8. Very nice.

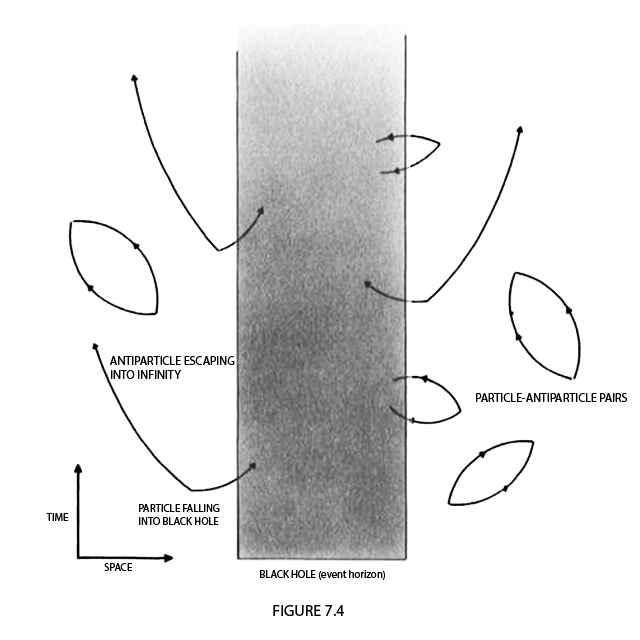

Regardless, I loved Hawking’s unapologetic and unpatronizing tone, as well as his humour. The physics was good, too, if also a little over my head (hence the re-read!). But that diagram of the particle escaping the black hole has stuck with me ever since, even if the text itself hasn’t.

Of course, in 2019, Katie Bouman developed the program, which was able to create the first-ever image of a black hole. So, and forgive the pun in advance, we still live in very interesting times, relatively speaking.

I only vaguely recall a handful of Canadian poetry books published in the last 20 years that I’ve read that had elements of hardcore science. And that’s OK. I never particularly sought it out. I like my non-fiction non-fiction. However, Natalie Zina Walschots’ DOOM: Love Poems for Supervillains scratched the itch in a way I’ll never forget; I never got around to reviewing Hench, to my chagrin. And Andy McGuire’s 2011 inaugural Baseline Press chapbook Sputniks had a very memorable binding, paper and cover. If I recall correctly, a Prussian blue string tied it together. Very suave, very chic. I’ve been trying to write science poems for as long as I can remember, but I think my largest contribution to the topic would be an unpublished poem from my diary 20 years ago where I romanticized the geology of beach sand. Leave it to the pros(e), I say.

Hawking has come up in my recent readings in Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), though. Philosophy professor and underrated conversationalist Graham Harman mentions the Theory of Everything in the introduction to his philosophy’s eponymous tome (2020) but ends up concluding neither Hawking’s theory nor string theory really account for everything in existence because the universe has more to it than physics.

The universe also contains Sherlock Holmes, war, Italy, sneakerheads, the institution of the Catholic Church, and enterprise cloud services. Quantum mechanics isn’t going to account for these sorts of people, places, and things, nor any abstraction on the various components making up Fermi’s laws of thermodynamics. The universe is materially more complex than that; ergo, Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology is, as he very admirably intones, “the only game in town” when it comes to discussing philosophy’s approach to a true and unified theory of everything writ large.

In logical terms, perhaps you could say physics is not a subset of everything, but everything contains physics. However, I’m already so far off track, back to Hawking and God.

Side-note: I have never read a Dawkins or Hitchens book—not my cup of tea. Charles Seife, Bryson, or Randall Munroe are more my thing. I like fun, I digress.

But, to conclude my intro with a word from our poet of the day, Eggertsen adds: the poems are about more than what’s on the tin.

So, let’s get into them.

The first poem is about the annual Vietnamese celebration of the arrival of spring, Tết, and everything that happens in this transformation of time, mood, and life as it happens around the narrator. Once again, we have a Canadian poet as a sort of fly-on-the-wall world traveller writing a poem of observation (R. G. Everson, Irving Layton, Al Purdy), although it’s always less impartial than the point-of-view would let on. The emphasis is always on the imagery, not the objectivity. This poem is a long poem that has a very abrupt break at the end of the first stanza to split and then conclude on a single line. I love the drama of that delivery and the way it reads, but I won’t spoil the line.

The next poem takes on a different tack: in the voice of Shirley Brockbank Paxman. I wasn’t familiar with her and searched for her name online. She has a very detailed obit but alas, I think the voice of the late Shirley might best be captured by the titles of her books: To bed, to bed, the doctor said: A book for families with lots of love and little patients (1975), Family Night Fun: A “How” Book of Family Activities (1963), The Family Book of Fun (1962), Party Patterns, with gaiety guaranteed: A book of complete party plans for adults and teens (1961), although her most printed tome must have been Homespun.

So, but this poem is about Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting of the mountains in Taos, New Mexico, and is dated April 1998 with the location of Sante Fe. So there is a bit of the deep south lore and mystical to it. I’m not religious but the nineties were a more spiritual time.

I was fortunate enough to visit the O’Keeffe and Henry Moore exhibition at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal last year, and I saw the impression her work has on his verse. O’Keeffe’s paintings, like Simon Peter Eggertsen, bear a certain admixture of reverence and literalism. What’s unreal is very obvious yet very delightful to the eye, and there’s a lot of real in it or behind it. Any geologist would admire a mesa painted by O’Keeffe; I doubt the same could be said of Henry Moore’s rocks.

The Hawking poem, I, of course, won’t spoil, but the poem wouldn’t be the same if it were about Blaise Pascal, you know? Too religious. I think it was the recent movie theatre adaptation of Hawking’s life where they revealed that Robert Graves was an early childhood influence on him. Very Joseph Campbell adjacent. I like Graves’ poems, I do. This kind of reads like one of his, marvelling at the wonder that was Stephen Hawking, cogitating, experiencing, perceiving in ways unbeknownst to the rest of us, like a demigod or mythical being of ancient lore or djinn. It begins to feel Borgesian as if we’re approaching the Aleph. A person is a place, perhaps, a memento mori of a mind.

There are still theories of Einstein that are being proven today by way of the Large Hadron Collider, telescopes and slide rules, or what have you. Hawking approaches God in ability and imagination, but personally? No. And that’s the best we can approach Hawking, by extension, the poet lets on; the rhetorical effect is resolute. We cannot know this god, direct intellectual descendant of Einstein and Newton before him.

It is mythological, isn’t it? And dark matter easily substitutes itself for whatever ether clogs up the New Testament. The whole subject matter is very fluid, but even though it’s only the fourth poem in the collection, I can see how nebulous and strong-weak this one poem ties the whole together.

This is something an Object-Oriented Ontology-informed critical praxis could express more routinely, perhaps. But I’ll drop the highfalutin nomenclature to say this much: it’s all connected. However, as a fellow heathen, I can say with absolute certainty: there’s no God in Hawking’s world nor mine—Spinoza be damned.

The next poem, “Lament for School Children and Wedding Guests” opens with an epigraph from Shah Jahan, whose name you may recognize from my review of Manahil Bandukwala’s Heliotropia, wherein a review of her previous work, Monument, deconstructed the legacy of the Shah and his Taj Mahal in an enlightening way that I now come to take for granted as one of the most canonical sources on the history of the place.

Eggertsen’s poem here is dated Afghanistan 2004, and is an elegy for three colleagues who died in a plane crash. The solo line in the middle of the page “We thought you would be here longer” is harrowing. And that’s the familiar pain of grief, of anger mixed with loss, to be on the road and surrounded by strangers getting married, or children erring on a field trip, about some landmark you already paid to go and see, and think to yourself: how did so many people outlive the ones I loved? None of them were old enough to die, look at all these folks around me now, complete strangers, but even I can tell none of them are old enough to die, either.

Life has a weird way of keeping the living young. Death always arrives too soon. There’s something unremarkable yet primordial in the Dari word he transcribes here, khub, meaning fine, well, good, that I appreciate (it’s one of the first words you learn if you study Farsi or any dialect thereof). The basics, the rudimentary foreign phrase, is all he has left to cling to of his colleagues gone too soon, which makes it all the more corecleavingly humbling. We keep next to nothing of the people we lose, even when we remember everything.

Section II starts with an inviting title, “My Father Sketches Out Our Ancestry, Threads the Space-Time Continuum,” and poeticizes the weird math of memory and family trees when illustrated by his father before his eyes, watching him poke the pencil through the nodes of the branches to thread a blue ribbon through and tie it off. The effect of the scene is felt. This is something sacred, like fate, the metaphor of astrophysics, the immensity of the universe and the implication of time as a dimension parallel to space undeniably immediate.

I’ll be direct: there are other Stephen Hawking poems in the collection. But I like this one that falls in between two of them in the second half of the book that I’d like to share here in full to let the poet speak for himself and because I’m a blogger, not a print mag, so pretend it’s open mic night and I’m reading:

on opening the earth

in Pho Yen District, everything depends on

a hulking, dull-eyed, wide-nosed buffalo,

trailed by the black-clothed farmer, when

they shuttlecock their way back and forth

over patch-worked fields, ply dirt into mud,

open the earth for all.

and, on a rickety wooden sledge—weathered

grey—filled with bouquets of spring-green

rice starts, sitting on its own shadow

at mid-day, waiting for someone to drag it

nearer the water-rich paddies.

and, on village women, wizened and young,

stooped like bent nails through the day, moist

to their soft hips, sliding slowly backwards

together across the earth-floor, skimming pools

of water, as they separate, lift and point

green-bristled stocks into a smooth surface,

change it to a hedgehog’s back.

no, a saffron-robed priest reminds us—once all this

work has been done, it all depends on the spring mists,

the will of heaven and earth.

—Pho Yen District, Vietnam, March 1997

I hope Simon Peter Eggertsen doesn’t mind, this poem has never been shared online. Excuse my belated spoiler alert. But Eggertsen is much himself a belated spoiler alert with his musings on life, aging and time. These poems excavate something profoundly personal from a culmination of exotic places and intersecting walks of life.

It’s rare to witness the emergence of a writer such as Eggertsen in any time period, in any country, in any lifetime. So, if you have a bit of time and cash to spare, I recommend you locate the latest of his works. Hawking Comes Close to Finding God is available through Turret House Press. Thanks for reading.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.