Sarah Burgoyne, The Tentaculum Sonnets

Sarah Burgoyne has a propensity to show off like this in every stanza of every page she works on, and it’s scary, talented and exhilarating to read.

Pardon the fan behaviour to start off this brief, informal review, but I feel as though it gives an important context clue: the inscription Sarah left me on the title page of her chap was “Thank you for supporting these shaky web-like poems!”

I remember thinking leading up to the launch of Mechanophilia that I really ought to get a book review blog where I can publish things at my own pace and deal with publishers directly like I used to do back in uni with my blog Literatured. I did not yet possess the experience of hard work back then, and although I had incredible support from the small press publishing scene nearly every step of the way, my review output was desultory for five years at best. I was still very green and still very much am.

But I live by the attitude that 30 is the new 20, and although I missed the chance to review Mechanophilia at launch (which happened 2 months before I first test posted on this blog and 5 months before I soft launched it), I still attended the reading and confirmed my suspicion: Mechanophilia was certainly my kind of book, what I sporadically refer to in my marginalia and sometimes public reviews as heady, with no intent of negative connotation. Math, pop culture, assonance and dissonance, elements of beat, flarf, and whatever. Eclectic and experimental, wide-reaching and deep-prodding. I may still review it one day.

But for now, I am looking at this beautifully square chapbook published by rob mclennan’s above/ground press in 2020. This pub falls between her Mansfield Press début collection Saint Twin in 2016 and because the sun released by Coach House Books in 2021.

The Tentaculum Sonnets are 9 pages long and bring me back to the days when I would receive similarly shaped Angel House Press books by Catherine Owen and Amanda Earl. Some of my most memorable, formative review material came from chapbooks of this length and size. I adore the format. An oversized peagreen flyleaf extrudes a half-inch right of the black-and-white-on-white cover, depicting a figure bowing its head clothed in a hooded garment adorned with various scientific figures of butterflies; it also resembles a newly polished nail.

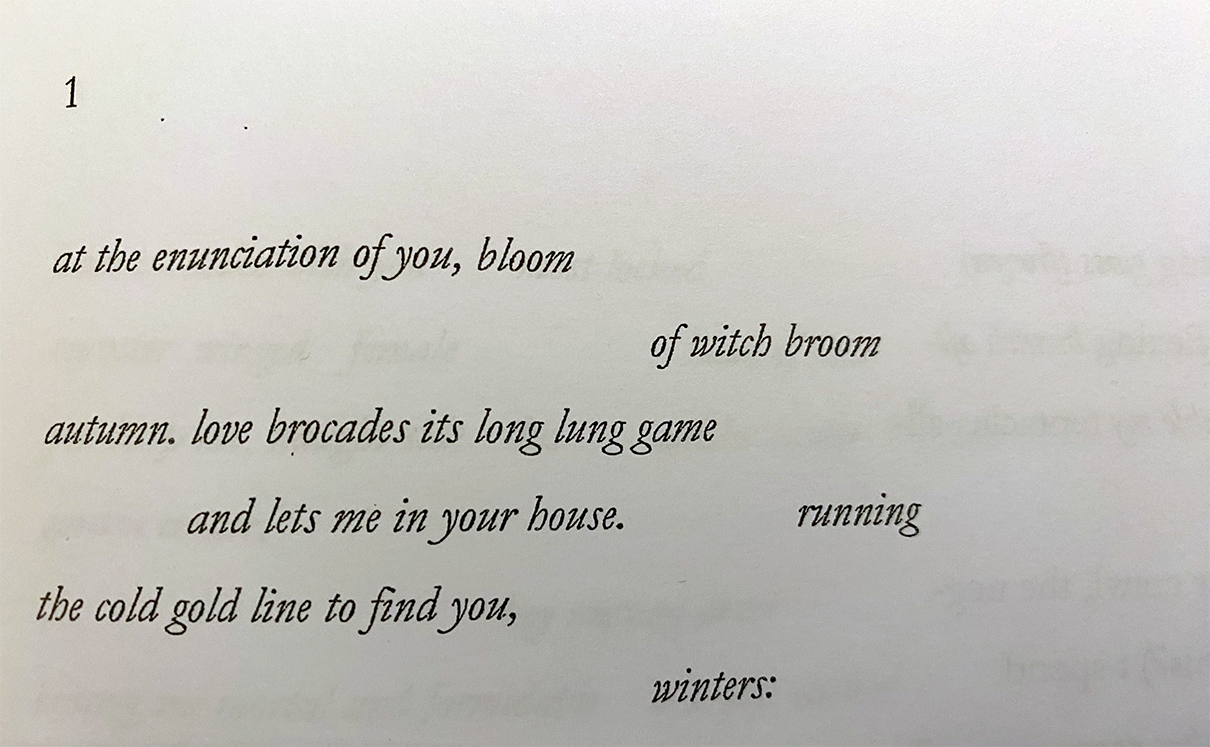

The first poem enters the frame with a halting screech:

at the enunciation of you, bloom

of witch broom

autumn. love brocades its long lung game

and lets me in your house. running

the cold gold line to find you,

winters:

Isn’t that devastating? Incredibly tangible nouns interhewn with devastating tones of implication, all held together by a kintsugi of vowel harmony. Don’t let me spoil the rest by typing it out, although it is the particular joy of being a reviewer to spoil things as I see fit. Email rob, buy this book.

Before moving on to the following sonnet, how does this first one hold up structurally? What is the poet saying with her commitment to the form and transgressions, if any?

The first six lines are in spaced-out italics, as reproduced above. The rest of the poem is a mix of emphasized and unemphasized words and 12 lines further, putting us at 18, not the expected 14. Ergo, the lines spaced out to appear after the preceding ones ostensibly count as one, which puts us back down to a total correct count of 14. Interesting.

Because what does it say for the rest of the poems in the sequence? And, above and beyond, what does it say about the sonnet in 21st-century verse? We are compressing too much to adhere to the ways of yore. The sonnet wants to break convention but revel in being recognized as what it once was. Different but the same, new and renewed.

Between ghazals and sonnets, I equivocate my faith more than an amateur astrologist who deliberates between moons and gods. Sometimes, the fad is a fad, but other times, we are dealing with an order of magnitude of engagement with form that transcends what publishing considers trendy in this day and age. By comparison, when you read Canadian anthologies or magazines from 2-3 decades ago, you get the sense that ghazals were more in vogue than sonnets. Now, that has changed. Maybe it’s a millennial calling card. I would ascribe Sarah Burgoyne’s work to the former, not the latter. Let’s listen to what she is and isn’t saying through her poetics.

Let’s look at another sonnet. Some in this series are more condensed, others more expanded. It is as though they resemble the variance in specimens on the cover of the work, each invoking their own contribution to chaos theory’s fluttering of wings.

As I rhapsodize, I realize: I have no idea what a tentaculum is. Sounds Nabokovian, in the lepidopterologist sense. In a sense, it’s a feeler, a whisker, and non-specific to butterflies, as it were.

As usual, Wiktionary is not enough. I knowingly head to my Annandale dictionary (extolled at length in my About page rigmarole).

Tentacle, tent’ta-kl, n. [L.L. tentaculum, from L. tento, to handle, to feel. TEMPT.] Zool. an elongated appendage on the head or cephalic extremity of many of the lower forms of animals, used as an instrument of prehension or as a feeler.

Related words include the adjectival Tentaculated, which means having tentacles, and my personal favourite of the batch, Tentaculiferous, which means bearing tentacles. Truly wonderful verbiage.

If I print any poem in full, I will feel like an imposter letting Sarah’s work speak so much for itself when I have elected to parse it for you, dear reader of reviews. So I will avoid it, but if I had to choose one, it would be the fourth or the sixth.

I may be biased. When I attended the launch in 2024, I was much more actively working on a manuscript of experimental poems involving rocket science, pop art and the history of cinema, which Sarah Burgoyne was happy to lend me an ear about. I’ve only discovered recently, writing reviews for other writers who’ve acknowledged her contribution to their work, big and small, how concrete her reputation as a good listener has been, unaware though I was of it at the time.

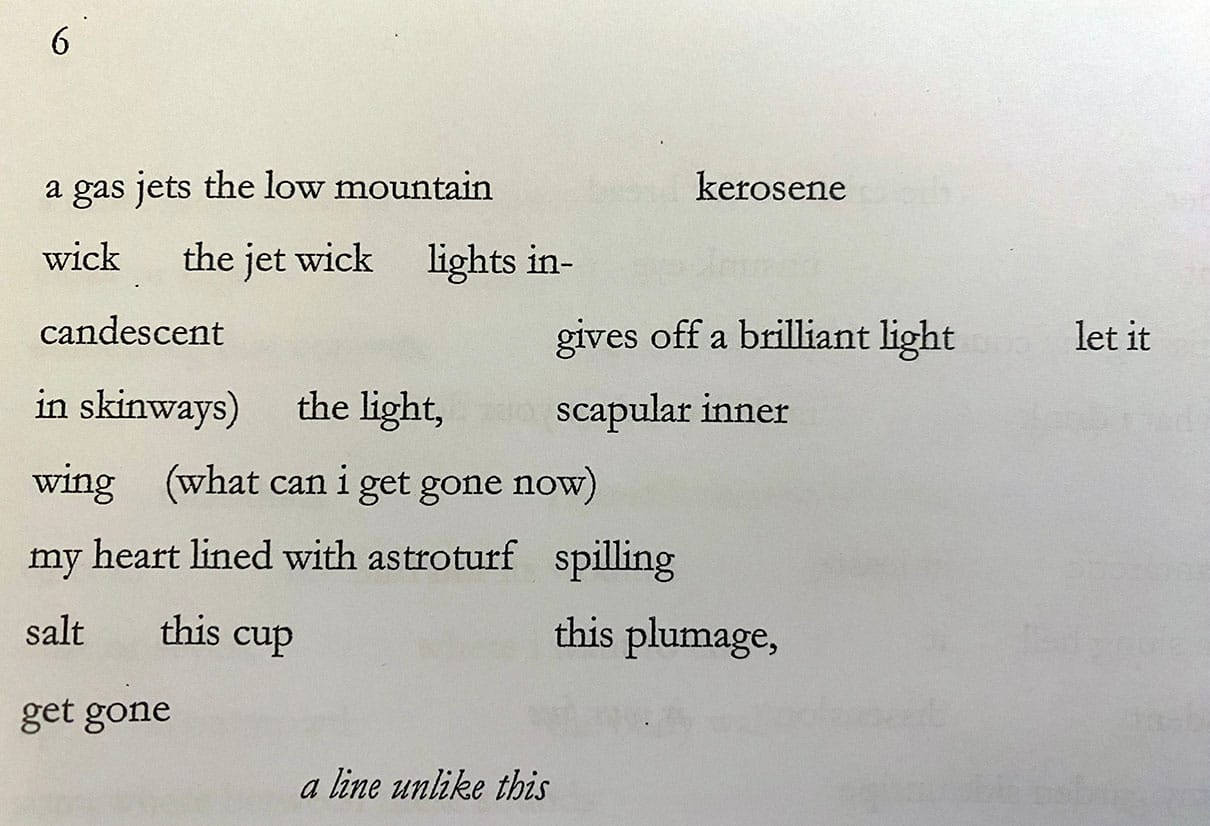

I have simultaneously made progress and doubled back since then, but that is perhaps why poem number six speaks to me, opening thusly:

a gas jets the low mountain kerosene

wick the jet wick lights in-

candescent gives off a brilliant light let it

in skinways) the light, scapular inner

wing (what can i get gone now)

my heart lined with astroturf spilling

salt this cup this plumage,

get gone

a line unlike this

So that’s the half of it. I feel like reviews abide too much by the guidelines. Reviewers should break magazine rules more often. Print the whole poem. Let us be the judge. Literature is expensive. But more than being cheaper (e.g. a newspaper costs less than a book), reviews can be fun.

What’s this sonnet about, however? How can I prove what there is to appreciate here beyond my gut instincts? What’s not being said? I’ll tell you.

It’s a setting of the scene, yes, this late into the story, six out of nine: we see the jets, we invoke the history of mechanical engineering involved in propulsion, the physics of combustion, kerosene, wick, incandescent, followed by these two inscrutable words: skinways and scapular (on the same line!). Bombastic. And where the hell did her end parenthesis come from? Perhaps the previous sonnet or an afterthought entered mid-sentence? In media cogitans as opposed to in media res.

What speaks to me is the handiwork behind the coinage of a line, such as my heart lined with astroturf, as a qualifier of the predicate. What is she describing? Who is the speaker of the poem? At this point, by nature of the syntax, we mustn’t assume it doesn’t matter but that the narrator isn’t actually revealing it. We’ll cross that bridge when we get to it. But on a purely aesthetic level, the metaphor that combines this line and the next is incredible, all connected by a gerund for a verb. It’s exquisite. An astroturf heart spilling salt; cup, plumage. It is animal, mechanical, physiological, chemical, gastronomical. It’s doing so much, painting this picture, and Sarah Burgoyne doesn’t even let us escape the complexity of this image by telling us what we’re gonna do with it. I’ll tell you what we’re gonna do with it: cherish it.

The beauty of any given poem, sonnet or otherwise, is its ability to broach the upper limit of complexity of sense. Whether it be by way of metaphor, rhetoric, aesthetic, irony, or narrative, so be it.

This one line accomplishes so much without necessarily abiding by the demands of readerly comprehension, the so-called “does it make sense.” It does, or can. But that’s not what’s important. It achieves a confidence of nuance that reflects the aesthetic consistency of the rest of the work while contributing material to the narrative.

Is it a fragmented narrative with nebulous personage and verbal coinage? Absolutely. But there is so much drama happening between these lines, which I will refer to neither as sparse nor terse because what they really are is vehicles that convey an emotional impact, a sense above and beyond literalism that I think a lot of readers our age fail to grasp the appeal of.

Sarah Burgoyne has a propensity to show off like this in every stanza of every page she works on, and it’s scary, talented and exhilarating to read.

Read Sarah Burgoyne, and you literally become the Ancient Mariner lost in the throes of a curse, in a frame story, in a pub, lamenting that damn albatross.

It’s Coleridgean narrative prowess mixed with a surrealist twinge. I don’t know how else to put it: spooky good.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.