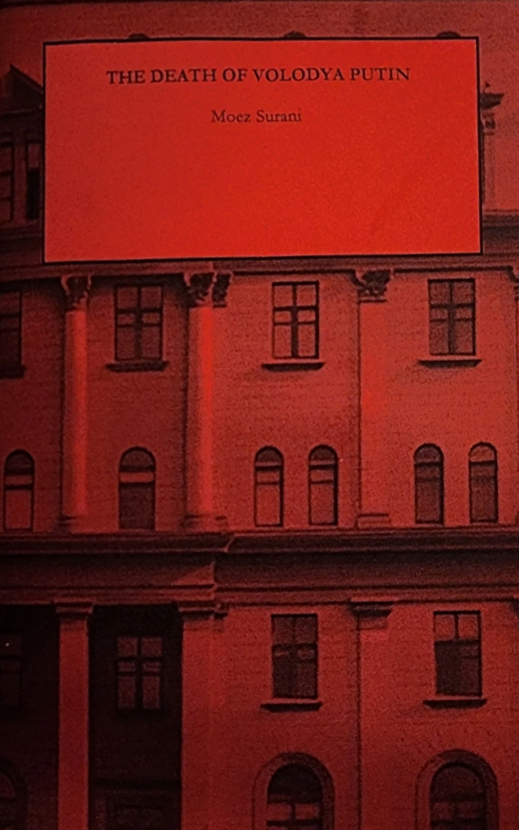

Moez Surani, The Death of Volodya Putin

Every line enumerated with a note, a reference, seems to be as confident, if not more so, than the last. But it is a purloined confidence, from the headline writers and lede buriers, a farce ad nauseum.

This little book (March 2025, No Press) has enough endnotes to cast a shadow over the spines of the Warren Commission books. However, it has a reading experience reminiscent of the more recent Mueller report, with nearly every reference appearing to have been published in the last 2-3 years, save for a half dozen or so from the last decade. But with a David Foster Wallace edge.

Moez is right. It would be uncouth to call Putin in the familiar by anything other than the textbook derivative Volodya. Vova is too familiar, and the only other formation, Vovochka, a diminutive of the former, “is closely associated with a long-running series of jokes featuring a naughty schoolboy.”

I’ll say this much: Surani is very smart. Reading these lines, asserted in uncompromising confidence, paints a peculiar portrait. Every line enumerated with a note, a reference, seems to be as confident, if not more so, than the last. But it is a purloined confidence, from the headline writers and lede buriers, a farce ad nauseum. It depicts a confident profile of uncertainty.

Various recent demonstrations included effigies of Volodya either behind bars or on the gallows. One, pulled along the main shopping street in Düsseldorf depicted him as a six-armed demon accusing everyone of being Nazis—Ukrainians, Americans, and Europeans included.

Maybe he will end up in a wheelchair like Pinochet, going to the High Court. Maybe he will be hiding like Saddam Hussein. Perhaps he will be an absolute vegetable like Salazar. But he will not have any other possibility.

This is the public history of expectation and has become a recurring theme with dictators worldwide.

Even this past month, there has been a rise in TikTok memes showing a sumptuous meal being prepared with the caption “this and getting the news alert,” the implication being that the news alert is that such and such a figure has died.

It has to be implicit because of the variety of filters and censures taking place across social media platforms, which siphon off a lot of the original content and regurgitate the middling tropes and clichés that got traction before.

Aren’t you tired of opening Instagram and seeing tweets from a Twitter that existed before Elon Musk? Or opening YouTube and seeing TikToks of something you liked and scrolled over three months ago?

This is public history. It’s not the history dealt with by historians, but it is the general consensus of relevant historical facts surrounding our current situation that we consume and the relevant facts that people peddle in to shape narratives into digestible assertions of power dynamics.

This is very much what Surani’s peristaltic book here aims to do: regurgitate the news. To paint a portrait of a dictator that may or may not be dead, a body double that may or may not be involved in a world-scale coup against democracy, and a war that may or may not end in Nazi or Roman emperor-like circumstances, with Volodya, not Putin, existing in this quasi-fictional realm of journalistic découpage, a quantum state of having a gun in his mouth, a knife in his torso, a cancer in his pancreas, steroids in his veins, shit in his diaper, and the looming threat of a black swan ever in his sight.

I thought Prigozhin was going to be the black swan. Maybe the black swan has already come to pass. But one thing is for certain: Putin—I’m sorry, I meant Volodya—will die eventually (if he hasn’t already).

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.