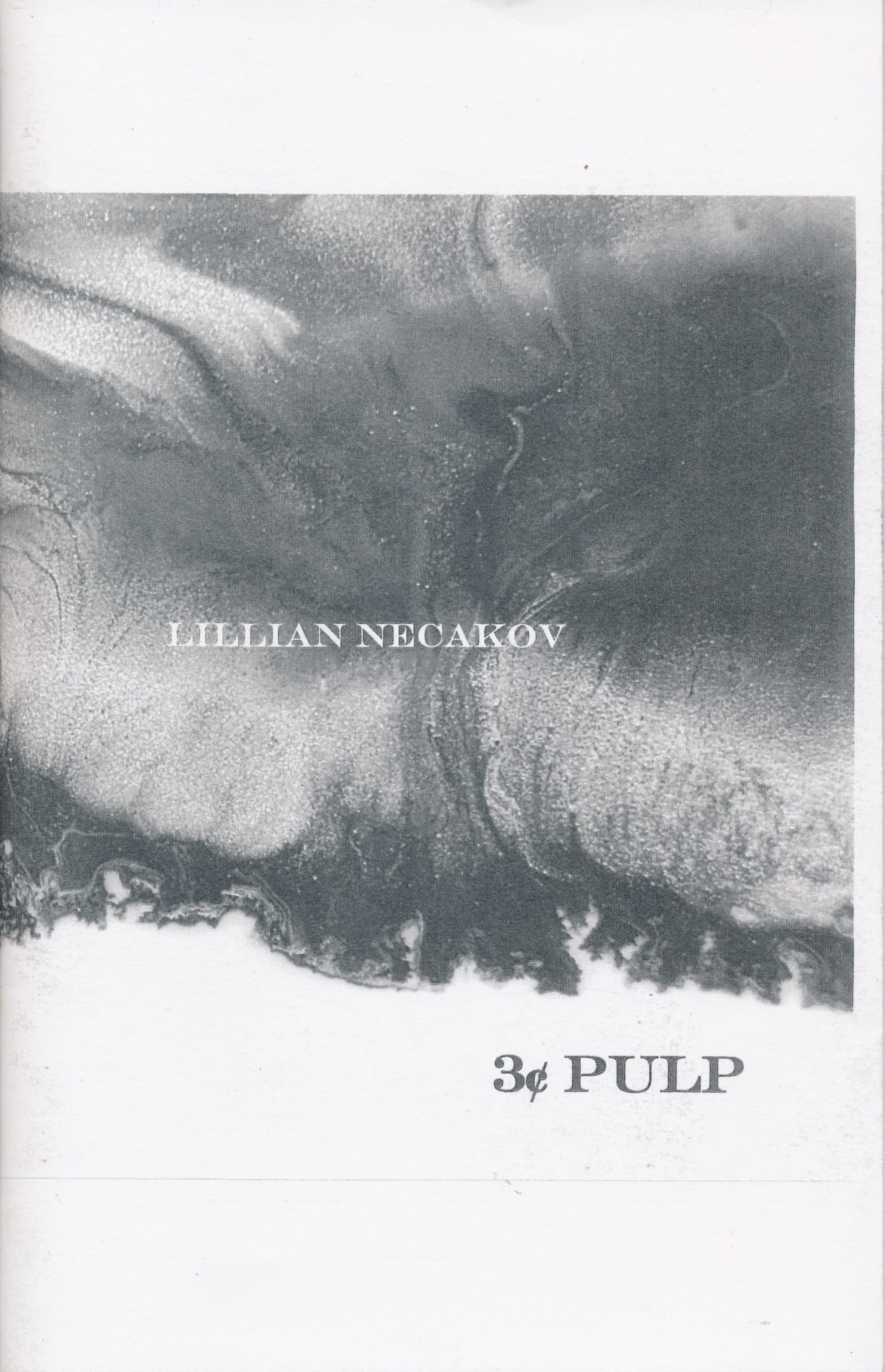

Lillian Nećakov, 3¢ Pulp

For a book so brief and light to the touch, it nearly brings a tear to my eye just to hold it and read quietly in my apartment’s warm and cozy solitude of afternoon weekend silence.

Lillian Nećakov is a sharp-witted, empathetic, and really cool human being. Her Mansfield Press poems, Hooligans (2011), introduced me to Mos Def’s Mathematics in a time of my life when I was listening to everything I could get my hands on of conscious rap-inspired songwriters like k-os and Buck 65. It sort of blew my mind.

The majority of her work I am woefully unfamiliar with and today is my attempt to rectify that lack of familiarity by reviewing her 2022 above/ground chapbook 3¢ Pulp.

Funny enough, she might be the only Canadian writer I can think of who bears a diacritic on the C in her surname, so seeing the cent symbol in the title of a chapbook of hers sort of makes me think of that. Is it a little inside joke about being Nećakov, perhaps, or am I reading too much into it? It’s probably actually something relating to philately.

I believe I was around to witness the work-in-progress for her 2021 collection, il virus, published with Anvil Press under Stuart Ross’s imprint A Feed Dog Book. The poems were published on social media during the 2020 lockdown in Toronto and widely shared and discussed if I accurately recollect. I look forward to revisiting those poems in an actual review someday soon.

But for the time being, let’s dive into the chapbook at hand.

The cover design is her own, and the inside of the chap has a ferocious pink flyleaf, front and back.

The first poem is preceded by an epigraph by Diane di Prima, an American beat poet, which reads: My friend walks soft as a weaving on the wind..., a line from the third stanza of her poem “An Exercise in Love”.

The first poem opens with a vivid setting of the scene:

When Birds Were Just Birds

for those who were...

1

Remember that time we were just kids

and so many of us were still alive

and we watched Lawrence of Arabia naked

in our small apartment on Isabella

It’s a poem about nostalgia and a kind of reminiscence in the form of an ode to her friends.

A beautiful line occurs several spaces below:

and sometimes we’d remember old streets

we lived on with brothers as subtle as lumberjacks

and we sat up late listening to records

on Steve’s old portable, a bottle holding

down the vinyl so it wouldn’t skip

we were Trotskyists and sometimes Partisans

but only for a minute

mostly we were poets in our tiny kitchen

and Yonge street

where voices and faces and the horizon

all came and went like snow

was enough

Then the poem concludes the next page over:

and we were just kids

and we never thought we’d end up

we never thought we’d end up

orphans

You couldn’t ask for a better closing line to an opening poem. Nećakov’s staying force, sense of dramatic build-up, and absolutely nailing the delivery is the same Nećakov I recall from all those years ago seeing her read at The Grad Club, where she read poems such as “Why?” and “Boneshaker” (the name of the bicycle on the cover of the Mansfield book, as well as of her former Toronto reading series).

More than empathetic, I have always found Nećakov to be sentimental. It’s a quality lost on most writers, I think. With the depth of her emotion and her undeterred ability to read the room with every poem and enunciate accordingly, it’s no surprise Boneshaker lasted as long as it did (2010-2020).

Jim Smith (a writer who knows the true meaning of love), said in response to Nećakov’s shuttering the series, “It was the very best, curated by the best, read at by the best, attended by the best! It will never be bested, and on behalf of the readers and the read-to, you are the best! Thank you for the incredible loving effort it was.” Smith and Nećakov go way back, of course (and I’m pretty sure is mentioned in the opening poem of this chap, “two friends named Jim”, in fact).

So that’s what this book is about, I sense. Three-cent, perhaps being a Canadianism for threepenny, speaks to Nećakov et co.’s Brechtian ambitions as young poets in Toronto in the seventies, etc. These are poems about friendship, celebrating what made every person unique, the grassroots atmosphere and intellectual era they shepherded into the 21st century, and so much more.

They are poems but could equally be considered tangible historical record for a period of time stretching two or three decades that has been abundantly documented yet haphazardly archived, that of the late 20th-century Toronto arts and culture, I mean; so many mementos and souvenirs in so many exhibits, documentaries and interviews, to which Nećakov has added a humbly sentimental slice of her own.

From the poem labelled simply “2” the next page over:

Remember when birds were just birds

and not a thousand ways to wish

for the body to stop being broken

and we cradled our books like dying girls

because there were never enough words

or skin to explain what we yet did not know

and some of us got married

and some of us got punched

and we wandered the streets shadow to shadow

under a softening sky

while the oak trees creaked and moaned the blues

all the way down Gloucester

where we ate pizza and talked about god and

sometimes Kurt Schwitters

and we tallied up how much we owed Charlie

at This Ain’t the Rosedale Library

for all those damn books we kept buying

and we wrote our childhood dogs into every ending

and sometimes our thoughts were as scattered

as grasshoppers

and we borrowed jars from Carlo the waiter

in an attempt to collect every last one of them

and hurried home to listen to their divinity

Every poem begins with the word “Remember”, sorta how David W. McFadden used to do it, borrowing the technique from Georges Perec, but interestingly putting the verb in the imperative, absent the singular first-person subject pronoun. It’s an intimate invitation to revisit the past with her.

The fifth poem opens with this incredible hook: Remember how it was before we met our heroes / each day a museum, I can’t help but linger on the opening lines, only to speed through the rest of the poem and arrive at the end too soon to prevent heartache:

and we remembered that one day we would sit Shiva

one day the tether would break

one day we’d remember how easily we forgot

This opening poem is 7 in total, in fact, but afterwards, the poems begin to have titles again instead of numbers but never shift in tone:

Zero Sky

for Gary Barwin

Remember telegrams and long-distance operators and that time they asked Beckett if he had any new year’s resolutions and he said;

resolutions colon zero stop period. And how I cut my hair and we drove to Hamilton in Shirley’s Reliant K for Beth and Gary’s wedding. [...]

This is Nećakov’s contribution to the Beat tradition, something that has always held a special place in readers’ hearts, I imagine. And she is true to the spirit of the letter, really. Toronto’s poetry scene really was a beat-like movement, in its own way, although the movement maybe transformed into an era as background characters gave space to the lead actors and the world stage lurched forward through time.

It is bittersweet to read Nećakov’s poems here, and realize simultaneously how fortunate we are to get this inspired series of anecdotes, with all the names and places sprinkled throughout like we know them as well as her, and she lets us, and how we will never have another generation of poets, so brilliant, so self-reliant, so unfettered, so raw, and so talented, ever again. For a book so brief and light to the touch, it nearly brings a tear to my eye just to hold it and read quietly in my apartment’s warm and cozy solitude of afternoon weekend silence.

Villanelles

after Mark Laba

Remember Mark Laba standing in the crow-black, in the crow-black eyes of Goya, always, standing, in the front rooms of John and Peggy’s, above the tailor shop while the Queen car lured 5 am doorways into sleep, standing in the Harpo Marx grins of slaughterhouses, in the 24 hour Freshmart on Church street, standing, carving villanelles into Thursday’s corned beef while the rest of us dreamed punk jesus swinging from the power lines. Remember too, those beautiful boys in stilettos with painted mouths, standing, waiting on the crow-black hearts of monsters, standing, in the jerk-off alleys behind the butcher’s, standing on unsteady legs, like spooked colts. Remember walking north, then south, and always ending up just west of the darkness but east of the light. Remember how every book was a holy cross, a bus out of here an un-hexing, a long nights’ journey into the sun’s holler. Remember decades later, standing together in two different cities, standing, on the shores of permanent wartime, surrendering to all those poets humming in their crow-black coffins.

I read this poem and feel momentarily speechless. I don’t expect most people to relate. Even though, as a reviewer, I should probably at some point slip in a sales pitch for the author at hand, if you haven’t already read any Mark Laba, him and Nećakov are really the take-home points of this review here.

When you’re done reading, go find their works; you won’t regret it, and better yet, you’ll know why I can’t help but shut up and share this poem. It is so Mark Laba. What a prize. All these poems are so good, but this one especially speaks exactly to everything I was saying above. I guess we can just leave it at that.

And John is none other than jwcurry, who also captured the scan of the chap’s cover used in this review.

It’s like Stuart Ross said in his Book of Grief and Hamburgers; I’m paraphrasing: sometimes you catch yourself grieving in the past, present and future tense, and you don’t even know what for.

The number of poets Stuart has introduced me to, on paper and in person over the years, Lillian included, is simply too many to count. Coming from a completely separate generation myself, I know the poets they remember are beyond too many, and I think that’s why, when you stumble across a quiet little black-and-white chapbook such as 3¢ Pulp, hiding its hot pinkness right behind its grayscale cover, you begin to understand the ethos of the group.

It’s not a clique. You’re allowed in. It’s a generation we’re in the process of losing one-by-one, and only a poet like Nećakov could pin down exactly what that feels like and how to lay it down in poems for everyone to reminisce.

The next time I'm travelling and someone asks me what Canadian literature is, this is what I’m gonna tell them it’s all about. Lillian Nećakov is walking-living-breathing Canadian literature. Or, in a word, to quote Jim Smith: Lillian Nećakov is the best.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.