John Metcalf, What Is A Canadian Literature?

What Is A Canadian Literature? is a thought-provoking work bearing a perspicacity utterly alien to the nimbyist pricks lording over CanLit.

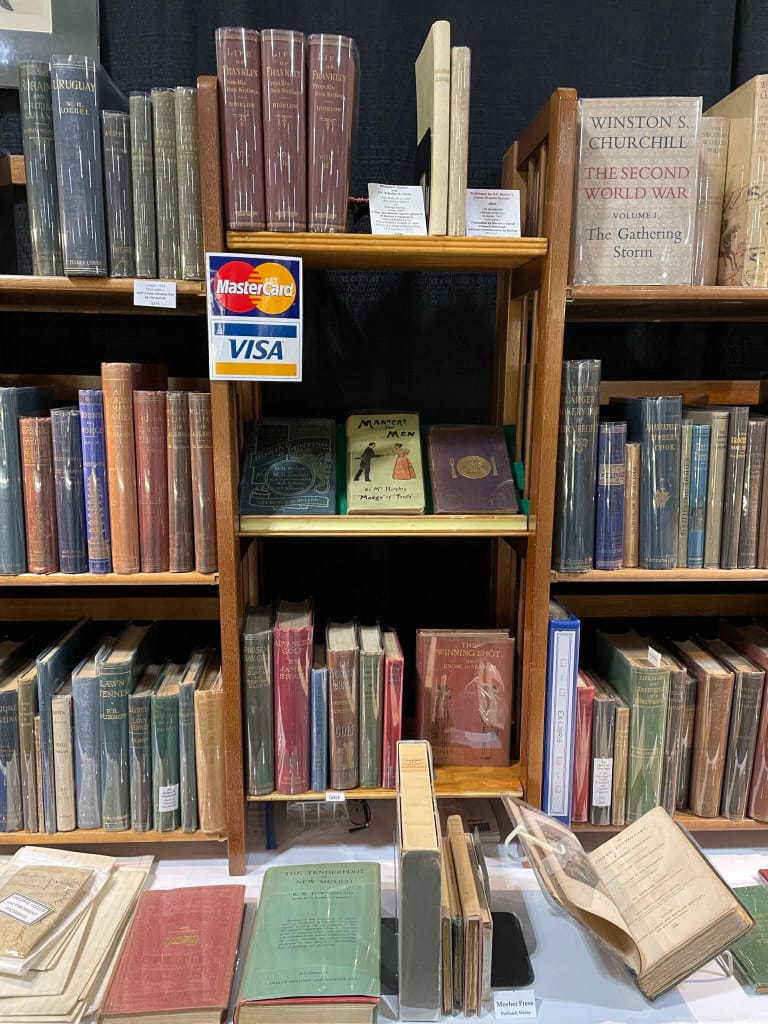

As a former book fair frequenter, over the years I have come into certain books which appealed to my younger, more precocious intellect. Books that, although I never chanced to read, the older intellect inside me finds new appreciation for. Finally having time later in life, or skill enough at last to evade distraction, to flip through these tomes, I find particular solace. It was worth holding onto all these years. Tomes like this in my collection are often my age or older, slender and frail, and not something you can always readily find in bookstores, libraries or online.

As an aside, on the matter of book fairs in Montreal, I tend to favour the Westmount Book Fair (Le Salon du livre ancien de Westmount) over the Concordia or McGill charity book fairs or any of the local library book fairs simply because of the calibre of literature you can happen upon there. All book fairs in Montreal cater to the tourist class of book hoarder, in my experience, which is my roundabout way of saying their prices often inspire the meekest among us to feign extroversion and haggle to lower the price.

However, you’re not gonna haggle the volunteers of any charity book fair, as most of the events associated with post-secondary institutions and libraries are not-for-profit by nature, often leaving the price-gouging antiquarians as a last resort to acquire any sort of valuable literature, outside of traditional second-hand bookshops and online marketplaces, of course.

But some modicum of appreciation for the supply chain is required to not come off brash in price negotiations with said antiquarians. Antiquarians seldom hit the road. Buyers typically come to them. The reason being: it costs a lot of overhead to show up to these events for booksellers, who already operate on a margin of profit invisible to the naked eye of most entrepreneurial types.

If you’re a bookstore owner, the best bang for your buck would be buying up en masse at the charity fairs themselves, whose organizers may be open to schmoozing depending on the quantity of paper you’re intending on transporting back for individual pricing. Better yet if it’s within city limits.

Conversely, if you’re the owner of a barcode scan gun, you really have no business cavorting with the rest of us literal bookworms, sellers and collectors alike, since we know what we’re looking for, ISBN notwithstanding (half of my books don’t have one, quite frankly). Because we have taste and pay cash. Because we know what we’re doing.

Ergo, you can’t lowball a price gouger on principle, when it’s really only gouging relative to you, the bookhoarding maniac that you know deep down you truly are. You have to compensate, you have to be harsh but fair, and you have to be willing to meet in the middle, with your ego as much as with their bottom line.

I encountered the owner of a warehouse recently and was immediately able to put two and two together as to how one might acquire such a volume of books in a lifetime. When I brought this up at home, my fiancée simply replied “no”.

It is absolutely not an expression of free will to be burdened by so many bouquins.

It is a duty and a destiny, above all. Pardon the grandiose turns of phrase here, in this aside, because for all the callings that are known in life, bookhoarder is perhaps the humblest, noblest, most expensive and most thankless enterprise anyone with money can ever endure. Books can break you if you don’t know when to let go. Therefore knowing your prices is navigating a two-way street.

And this aside comes full circle, as it happens, to my review here of John Metcalf’s 1988 essay, What Is A Canadian Literature?, published by Red Kite Press in Guelph, Ontario (and available with a free account through The Internet Archive).

The title really stems from his perennial lean into the national political implications of our literary press scene, which is important, but a recurring tune from Metcalf. In 2022, he published his less obvious sounding title Temerity & Gall with Biblioasis press, although the waspy Anglo-Saxon and Old Frisian undertones are right there in the etymology of the words if you’ve got the eye or ear for it.

And having read his essay published more than 30 years prior (which I’ll refer to going forward as What Is? for short), I look forward to reviewing Temerity & Gall down the road coming up.

However, What Is? is an essay centered not so much on what makes CanLit Canadian so much as it is on a conspiracy of delusion in the academic press of the country over the span of many years of collective cognitive dissonance.

In spirit, it is reminiscent of a work by Donato Mancini, You Must Work Harder to Write Poetry of Excellence (2012, Book*Hug), a book I attended Donato’s launch of at Librairie Le Port de tête here in Montreal many eons ago and whose reading left an indelible impression on me as a reviewer.

The title of Mancini’s work deliberately mocks the national ethos of roughly a century of Canadian literary criticism that essentially boils down to “if I don’t get a poet’s book, label them bad capitalists and move on.” Which, beyond being hypocritically lazy, also shouldn’t be your metric for assessing the goodness or badness of a book. Scansion, hermeneutics, sociology, or comparative analysis are all valid methodologies, but the end result should constitute more than just “I’m unimpressed, the poet didn’t work hard enough” not because it’s reductionist to say that (which, albeit, it is), but because at the end of the day, saying that in a book review doesn’t explain anything. It doesn’t show its work. That’s just doing the work of capitalism, and capitalism is just sparkling colonialism with a shiny monocle, i.e. support the colony or perish.

Basically, Metcalf’s drama focused on the overblown importance attached to a work of not only minor significance, but meagre impressions, circa 1896, namely In The Village of Viger by Duncan Campbell Scott.

Metcalf goes on to demonstrate that, since the beginning of commentary on this book took hold, no professor or critic has turned down the opportunity to elevate the regard and empty praise associated with the work. The broken telephone of bandwagoning reached such a point that Scott’s work got anthologized and listed in encyclopediae as a work of life-or-death import on Canadian literature as a whole, going so far as to claim its influence over more than a half dozen of some of the biggest names of the 20th century in Canadian fiction and verse. More to follow shortly on that thread.

In a particularly joy-inducing passage, Metcalf mentions a familiar name in the book bargaining game:

Nelson Ball, in Paris, Ontario, another of the best-known dealers in Canadian first editions, says that he has never had a copy of In The Village of Viger and adds that copies of Lyrics of Earth and Matins he has handled have all come from dealers in the United States and never from Canada. He says he would describe Scott’s book as ‘rare’.

Metcalf not only deals with the exegesis of comparison on one front, but on the other, gets into the brass tacks of accounting done for the original printing of the publication, and deduces that:

If we add these facts and likelihoods and hints together and err heavily on the side of generosity, we could say that perhaps 50 copies of the 1896 edition entered Canada and that between 1945 and 1970 The Ryerson Press sold 350 copies of the reprint. This gives us a total sales figure in Canada of 400 copies in seventy-four years.

So, even on a logistics front, there is no way this 152-page book of gaudily worded settler tales could have been responsible for the “birth” of modernism, realism or the short story, or the village story, or whatever other convenient circumlocution used by writers otherwise branded as clever to cover their tracks for lack of proof or facts.

Metcalf quotes Wayne Grady’s introduction to The Penguin Book of Canadian Short Stories, 1980:

The Canadian short story as literary art form wasn’t born, however, until 1896, with the publication of Duncan Campbell Scott’s In The Village of Viger. If one thinks of Gogol and Poe as the twin parents of the modern short story - Poe representing the imaginative, fantastic side of the family, Gogol sticking closer to earth - then Scott’s collection of ten realistic short stories about the residents of an ordinary French Canadian town is the salient indication of the branch the Canadian story was to follow. [...] In the Village of Viger, as a series of thematically linked short stories, looks back to Gogol’s Evenings Near the Village of Dikanka - though with obvious nods in passing to Flaubert and de Maupassant - and ahead to Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, Margaret Laurence’s A Bird in the House, and Alice Munro’s Who Do You Think You Are?. Scott is what the genealogists would call a gateway ancestor.

Wayne Grady spoke on finding out his real genealogy at 47 at an event I was covering for the Kingston Writers Fest in 2013 (roughly 15 years after writing this introduction), making his own choice of words in the concluding line above come off as more ironic than unfortunate, in a way I’m sure even he must recognize the humour of.

Metcalf goes on to conclude this middle section of his work by chatting up the growing list of living contemporary authors (at the time) alleged to have borne the “unobtrusive influence” of In The Village of Viger:

Hugh Hood, Alice Munro, Sandra Birdsell, Edna Alford, W.P. Kinsella, George Elliott, and Jack Hodgins.

Of these seven writers cited as being in the tradition, not a single one had read the book. Not a single one had heard of it.

Hugh Hood said: “I would actively resent any association of my name with In the Village of Viger.”

Alice Munro said: “Tell them that the book that influenced me was Winesburg, Ohio.”

Sandra Birdsell said that her main influences were Sherwood Anderson, Flannery O’Connor, and - most interestingly - Alice Munro.

Edna Alford had never heard of the book.

Nor had W.P. Kinsella.

Nor had George Elliott.

“Was he the one,” said Jack Hodgins, “who wrote stories about bears and - was it wolves?”

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I think from the sound of it that was G.D. Whatsisname.”

Jack Hodgins went on to say that for him as a child in British Columbia, Scott in Ottawa would have been as foreign as a writer in Mexico - and just as far away. He also said that he thought the traditions of most Canadian writers were not Canadian at all, that most Canadian literary traditions were invented by academics retroactively.

Metcalf at one point makes passing remarks on his being accused of rewriting literary history to make it convenient for “the” CanLit tradition to include him, a writer born in 1938 and immigrating to Canada from England in 1962, as a Canadian writer.

If the institution of CanLit really wanted a village tale from the Canadian tuxedo-coded neck-of-the-woods featured in Viger, the French Canadian novel Maria Chapdelaine by Louis Hémon (a Breton novelist turned Canadian) was right there this whole time. Hémon actually proved demonstrable impact on Quebec literature while providing a realistic portrayal of rural Quebecker livelihood, in a short novel that could be described as a turn-of-the-century Hallmark movie, essentially.

Maria Chapdelaine has been visibly lionized across the Francophonie for the past 100 years (I acquired my copy from a bouquiniste amongst the marchés de plein air of Paris no less), more widely than Under the Volcano (published 1947 and out of print during Lowry’s lifetime by his year of death, 1957, until a film adaptation appeared in 1984, along with a paperback reprint bearing the cringe-ass movie poster as its cover) and The Tin Flute (notable for winning the geegee and the hearts of Americans) in all likelihood. I could be wrong to assume, of course.

Then again, who are we kidding? CanLit doesn’t speak French.

Metcalf then expounds several pages later with some of the most refreshing and delightfully relevant prose on the topic as I could have possibly hoped to encounter, as a book reviewer and hoarder:

Our cultural nationalists fear that this will spell the end of the possibility of a literature distinctively Canadian. But being ‘distinctively Canadian’ is not, of course, a literary concern; it is political. It is possible to be ‘distinctively Canadian’ and thoroughly bad. Indeed, a writer’s intention to be ‘distinctively Canadian’ almost ensures lugubrious awfulness.

He continues shortly thereafter:

The one point MacLulich makes with which I’m in agreement is that Canadian literature “exists in a state of permanent crisis.” That state of crisis, however, has nothing to do with “being overwhelmed by outside forces.” “Outside forces” are not the problem at all. Internal forces are the problem. Canadian literature’s permanent crisis is that there exist very few Canadians willing to read it.

Personally speaking, as someone who was eager to implement Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology into literary criticism, Metcalf’s particular brand of investigative non-fiction work where he plays equal parts journalist, historian and critic represents so much more value to analyzing literary canon as object, than, say, Harold Bloom (whom Harman cites, in his book about architecture as object) for his 1994 work The Western Canon (a book I DNF’d after his deliberate conflation of Montaigne with Molière to repeat his broken record thesis that “everything’s Shakespeare”).

If you’ve been compelled by my previous ramblings and musings on Harman and Object-oriented ontology (aka “triple-O”) to read any of his philosophy, you may perceive a stronger resemblance to the matrix of Harman’s thought process and turns of phrase in Metcalf than in Bloom. Understandably so, because Bloom is likely more recognizable by name to the American Harman than Metcalf, the Canadian writer from England, who is likely unheard of by Harman. (Technically, OOO is a tool or perspective, not a school of thought, so any author could be understood through the mould of Harman’s fourfold, but we’ll save that for another time when I review Bloom and Harman, later on, separately).

Metcalf quotes himself towards the end of What Is? from his 1987 pamphlet Freedom from Culture:

A country’s literature is not a collection of books. A country’s literature is not contained in the holdings of the National Library. A country’s literature cannot be represented by a paperback reprint series nor can Histories or Companions chart its depths and reaches.

A literature is a relationship.

A literature is a relationship between books and readers. It goes back into the past and looks towards the future. A literature is those books which readers hold in their hearts and minds. A literature is made up of those books which the collective readership through time loves and deems indispensable.

What books do Canadians hold in their hearts? What are the books that all Canadians have read and loved? What books from the Canadian past live on with us? What, simply put, are our books?

Wacousta?

Why hasn’t a Canadian Literature come into being? Why, after thirty years of state encouragement and massive subsidy, is the literary relationship so attenuated and uncertain?

It’s funny what another 30 years of same old same old can do to hammer home the underlying truth of such an observation.

If you get past your worry that Metcalf is actively rooting for the end of grant money or PLR cheques, you have to actually read his book, because he’s not, on principal or as a matter of fact, doing that.

But what Metcalf is saying is that federal subsidy and being happy with stagnating domestic print runs simply cannot stand as the be-all end-all of any nation’s literature; before the Canada Council was founded in 1957, a holistic literature of Canadian origin was emerging on its own terms, according to antiquarian bookseller and specialist in Canadian first editions William Hoffer.

If anyone my age or older is still reading along what I’m writing here, then you may be relieved to see some familiar and still relevant names appear in the unfortunately titled periodical that Metcalf cites from Hoffer’s catalogue at this part in his essay.

Indian File (a phrase I only encountered for the first time here in Quebec French, and had to look up the meaning of, just last week), between 1948 and 1958 lists the following best poets, arguably the last nomination of national writers of import to appear in the decade before the formation of what would become the Canada Council for the Arts:

- Deeper into the Forest, Roy Daniells (1948)

- The Strength of the Hills, Robert Finch (1948)

- The Red Heart, James Reaney (1949)

- Of Time and the Lover, James Wreford (1950)

- Border River, A.G. Bailey (1952) [Alfred]

- The Colour as Naked, Patrick Anderson (1953)

- The Metal and the Flower, P.K. Page (1954)

- Even Your Right Eye, Phyllis Webb (1956)

- The Deficit Made Flesh, John Glassco, (1958)

Now, I mentioned Webb for the first time in my career here last year in my review of Manahil Bandukwala’s works, so that name I recognize; P.K. Page was brought to my attention for the first time as a reviewer by Porcupine’s Quill back in 2011 when I was starting out. The only other name on the above list that rings a bell to me, me having been born in the early ’90s, is Glassco, but I have only ever read his Poetry of French Canada in Translation, I think, when I was initially stockpiling my print resources as intrepid book fair connoisseur and wannabe reviewer around the same time as I encountered P.K. Page.

I appreciate the rhetoric of recapitulation in Metcalf: “Lᴀᴄᴋ ᴏғ ᴀᴜᴅɪᴇɴᴄᴇ is the centre of our problem. Nationalism is no answer.”

Funny, too, perhaps, because then he concludes on an appeal to our national sport, hockey:

There are good reasons why Canada produces fine hockey players. For each hockey player who achieves national fame, there are thousands of boys who live and breathe the game, watch every match, who pore over the hockey cards in bubble gum packets, who play passionately and with burning ambition in streets and alleys until the light fails. And there are mothers and fathers who sanction and foster this ambition, forcing themselves out of bed to drive these boys to practices in the morning dark, forcing themselves out at night to coach and cheer the little leagues.

A great hockey player emerges from a hockey world.

He continues after explaining the metaphor:

It is at present rather difficult to read a Canadian book without feeling faintly virtuous. Our present “culture” is a subsidized and legislated culture; it must become, however narrowly, a possession of real people...

And more convincingly on the last page: “Would Evelyn Waugh have washed his hair with a shampoo called Gee, Your Hair Smells Terrific?”

No, of course not. Readers and writers alike should not vie for mediocrity, nor abide by 2-in-1 shampoo-conditioner products. But that’s really what a bulk of the literary output in the past several years seems like sometimes in Canada.

There are other salient remarks and words worth sharing by George Bowering and Margaret Atwood in this volume, but I genuinely do recommend reading it for anyone hearing of it for the first time here or folks who may have already read it, so as not to milk it for every conceivable joy it contains.

Coming in at 104 pages, this Oberon Press title makes a formidably relevant argument with obvious implications and cultural political assessments that could not be more germane to the milieux we as Canadian readers, book hoarders, sellers and writers presently inhabit. Look, I’m even writing like him a little bit. The impact is undeniable.

To address Ken Norris, whose poems I will be reviewing here eventually (we share a publisher in common), for his review of, or really response to, Temerity & Gall, can I with all due respect just say this: don’t take the phrase “CanLit is dead” too much to heart.

Don’t mistake Metcalf’s evident upbringing and commitment to maintain a tone of levity as mindless proselytism. Also, don’t be a chickenshit.

In Metcalf’s context, it’s clearly a metaphor meant to imply that CanLit as a concept is a closed one ready to be curated and deconstructed for analysis, in the same way as still life painting in French is called “nature morte”. CanLit is not a living, growing, changing object in constant, quantum flux—it’s a phenomenon we can readily size, measure and document.

The “is dead” formation is something so commonplace, I myself use it in the about page for this blog even, as shorthand for “you may either believe in the format or not, I, from experience, personally do not, but I’m writing one regardless.”

If anything, it’s Ken Norris’s phrase “if we had a Can Lit that worked” that deserves a Donato Mancini-esque unpacking.

30 years ago, Metcalf was mourning the emergence of a financially independent Canadian literature. Let him say it’s dead if he wants. That’s not the point he’s trying to make.

By inference from Ken Norris’s review, all I can make out is that Metcalf has found no reason not to double down on his opinions from What Is?

But Ken says much more that overlaps with what Metcalf has already said 30 years prior, and I’m not convinced he’s truly miffed with how Metcalf has framed it. Ken Norris writes:

In my essay, “Louis Dudek & The Five Missions” I discuss the education I received from Dudek about how to be a Canadian author and a cultural player. Much of what he taught me was based upon the fact that, when he was a young author, there was no cultural class in Canada—therefore, authors had to perform all functions. Not only did they have to write their own poems, stories and books, but they had to serve as magazine editors, book publishers, reviewers and teachers in order to see that Can Lit had some kind of an existence in Canada.

[...]

As far as I am concerned, booksellers are a big part of the “cultural class.” Once upon a time, in Montreal, we had The Double Hook bookstore. No more. Adrian King-Edwards and The Word certainly come to mind. And Paragraphe is a delightful store. Generally, Chapters/Indigo is everywhere, and independent booksellers are hard to find. I am not satisfied with Heather’s Picks, which are like Loblaws telling the consumer what cheese to buy. Canada needs a lot of work in this area.

In short, to write a decent lede, Norris played the role of Chicken Little in the opening of his article, something Metcalf is aware he often inspires his critics to do (because he quotes them on it in his book).

But if Ken Norris really believed Metcalf was mistaken to claim “CanLit is dead”, then he’d be missing the substance of Metcalf’s message: Canada can subsidize, praise, revise, nationalize and evangelize as much as it wants, but the truth of the matter is no Canadian reader wants to read “CanLit”, or shouldn’t anyways. They should just read “lit”. In other words, Canadian people aren’t reading books written by Canadian writers as much as cultural nationalists might care to admit. And guess what kind of writers the Council prioritized their subsidy of first?

Look around what’s going on with mainstream and social media nowadays. Marshall McLuhan would be as exalted online as Bernie Sanders and Jon Stewart if he were alive in today’s media climate, recast for a second act as a content creator, perhaps. John Metcalf is basically John Oliver to CanLit at this point, an annoyingly convincing reporter of facts with textbook dandy charm. Everything, including American media (CNN, NBC, even American-owned papers in Canada), has been pointing to the fact that, when provoked, Canada falls back on its nationalist roots. Even Quebec! Especially Quebec, even. Everyone in Canada—except Wayne Gretzky, of course.

But for people who have spent any amount of time here before Harper, the beer commercial guy Warholianly summarizes the cultural ethos across the generations. We are Canadian, therefore don’t buy American, buy Canadian. When you go to the grocery store and see an American product, turn it upside down for other patriotic shoppers to distinguish it from domestic and imported goods. Similarly, as my grandmother, a former bookstore owner in Kincardine, Ontario, would have suggested: when it comes to books, don’t buy American authors, read Canadian.

It’s a tired take.

And I think this tendency to meretriciously glaze Canadian patriotism (an ism so American in origin it should be considered an oxymoron to duct tape Canada to the front of it) makes Metcalf’s message fall on inattentive ears, simply because... well, as far as we know, Canadian writers simply aren’t paid to hear that.

If anything: elbows down, read a book.

Metcalf’s not advocating for the backing of any Byronic cultural nationalism. That’s politics and he’s talking about literature. Canadian readers easily get caught up.

To fall back on my trusty Graham Harman (an American philosopher whose first book I read was published by Penguin in England), under the auspices of object-oriented ontology, arguably, political knowledge doesn’t exist, at an epistomological level. Which I think is why when anyone talks about Canadian literature in any context, there is a tendency to applaud the winner by who opines the loudest. Cultural nationalists get worked up about politics, which really shouldn’t be flattening discourse whenever we’re talking about literature in Canada, it should be relegated to duly annotated footnotes.

It wouldn’t surprise me if there were a heavily pertinent broadcast of The Debaters to illustrate my speculation here. But I’ve been to readings of books I’ve read, and in my experience, people miss the majority of irony on the page when they have to hear it for the first time with their ears and not in the silence of a reading chair.

Who else would be reading Metcalf than ultra-literate Canadians? By ultra-literate I don’t mean smart or well-read, per se, I mean “reads more than the average bear”. It’s hard to find fault in the opinionated opinions of his critics, they seem to know so much. But as much as I respect Ken Norris’s verses of late, and see a measure of truth in his response to Metcalf’s 2022 work, I also sense a mildly misguided knee-jerk reaction in Norris’s response.

So what if CanLit’s dead? If CanLit’s dead, Metcalf certainly didn’t kill it.

To quote a formerly prominent Brit in Canada, Jagger, it was you and me.

I won’t quote what Bowering said to Metcalf, though, I promise. But if you’re uncompelled to check out this particular Metcalf book, I will spoil it for you by paraphrasing: Bowering agrees with him. A Canadian writer can be any writer with citizenship. Why not? That’s not the question on the cover, though, is it?

What Is A Canadian Literature? is a thought-provoking work bearing a perspicacity utterly alien to the nimbyist pricks lording over CanLit.

A lot of the themes of the work and topics broached in his essay are familiar to me from experience as a book collector, reader, reviewer and Canadian. These are topics I haven’t ceased ruminating since launching my initial book blog Literatured circa 2011, nor even in the nearly ten-year-long hiatus I took from owning a blog since running out of steam to write for it around 2015.

There are four types of reviews on the chart of good and bad: a genuine good review, a genuine bad review, a dishonest good review, and a dishonest bad review. I have written at least three of these kinds of reviews in my time, some more than I’d care to admit. But it’s not the be-all end-all. I still think reviews are important.

But where I used to feel flattered by solicitations from authors and agents to review their pubs, my most honest reviews have only ever come from interactions that I initiated with publishers or authors themselves, and better yet when those interactions were first founded in a relationship created between myself and their books, magazine articles, or appearances in anthologies or in public.

There are editors and publishers out there who have spent their entire careers aware of these cross-currents in the culture and have doled out admirable generosity humanizing what books we produce as a country.

They will always have a special place in my writing, their work is undeniably vital. And I don’t think Metcalf would disagree, especially in the way he writes that allow us as readers, as book sellers would say, to “pick his brain” about his who’s who and what’s what in Canadian publishing.

Metcalf knows what he’s talking about and his perspectives are well-founded, even if they’re inconvenient to academics who invent swamps to create canons or to foreworders who hawk nationalism to make careers. Even Ken Norris admits how painfully aware he is of what Metcalf accurately observes.

I’m actually so sick of the idea of “CanLit”. It’s a phrase (along with “survival”, a morpheme so deeply rooted in colonialism and delusion it’s virtually synonymous with “CanLit”) I have actively avoided almost as long as I have avoided American books throughout my life.

People don’t want canned lit, they want a literature that can.

🚨 WARNING POST-HASTE ON THE DOUBLE DOUBLE, EH 🚨

If you have any grievances about the above-employed wordplay, please take it up with the Massage guy, or the remaining knowers of FILE (generously funded through the support of its subscribers, advertisers and the Canada Council for the Arts).

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.