Jessi MacEachern, Television Poems

The thing MacEachern gets about ekphrasis and TV is that these poems work like easter eggs: if you’ve seen it, know it, and then read the corresponding poem, it can be a portal of discovery.

This weekend in Montreal, Jessi MacEachern, author of the 2021 above/ground chapbook Television Poems, will be launching her latest work Cut Side Down. It’s a party and you're all invited.

Her publisher, Invisible Publishing, describes Cut Side Down as “a false autobiographical engagement with desire and memory,” and could, by an elongated stretch of the imagination, be seen as a technical extension of the approach used for Television Poems, so now seemed as good a time as ever to proverbially crack the thin stapled spine of this deliciously purple book of poems.

On her Instagram, MacEachern has an excerpt of a review by Manahil Bandukwala in Quill & Quire for her début poetry collection A Number of Stunning Attacks, also 2021, and also with Invisible Publishing, which reads:

MacEachern taps into what poetry does best, which is to bypass logical explanations and dive into an emotional core that here sings of strength above all. Whether the poems aim to draw attention to the interrupted nature of a gendered existence, or uncover a beauty to be embraced in deconstruction, the collection brings a new dimension with each read.

These poems, each of which captures a TV episode wherein poetry is featured in a manner the poet herself describes as “ekphrastic,” speak to me. Granted the suspension of disbelief (Coleridge!) as to why this review is not appearing sharply at 7 am for my newsletter subscribers, quite honestly, I was enjoying a triple feature of Mrs. Doubtfire, My Spy, and No Time to Die with my partner till the wee hours of the morning last night, and am now throwing aspirin and coffee back listening to FKJ do some funky stuff on the keys in “Live From The Greenhouse” to take my time and give Television Poems the attention it deserves.

Suffice it to say, media rules everything around me. Curiously, MacEachern writes: “After all, television is also an art form. It has no national month (as far as I know); of course, this may be because it doesn’t require the publicity.”

When I think of TV, I can’t help but think of Twitch City, a two-season CBC show from 1998-2000 starring Don McKellar and Molly Parker, and, at the time of writing, is available to watch in its entirety on YouTube. Don McKellar’s character, Curtis, is (more specifically than a TV addict) a Jerry Springer addict, although the show uses the stand-in of Rex Reilly for Springer in the series’ fictional canon. He is a fanatic and his unwavering love and admiration for Reilly exemplifies the surrealism of Toronto existence in entirely unexpected ways.

If Montreal is Canada’s ekphrastic city par excellence, Toronto is very much Canada’s surreal city ipso videlicet demonstrandum.

Bref, Jessi MacEachern may very well be to ekphrasis what Don McKellar is to surrealism. Hold my pineapple cookies.

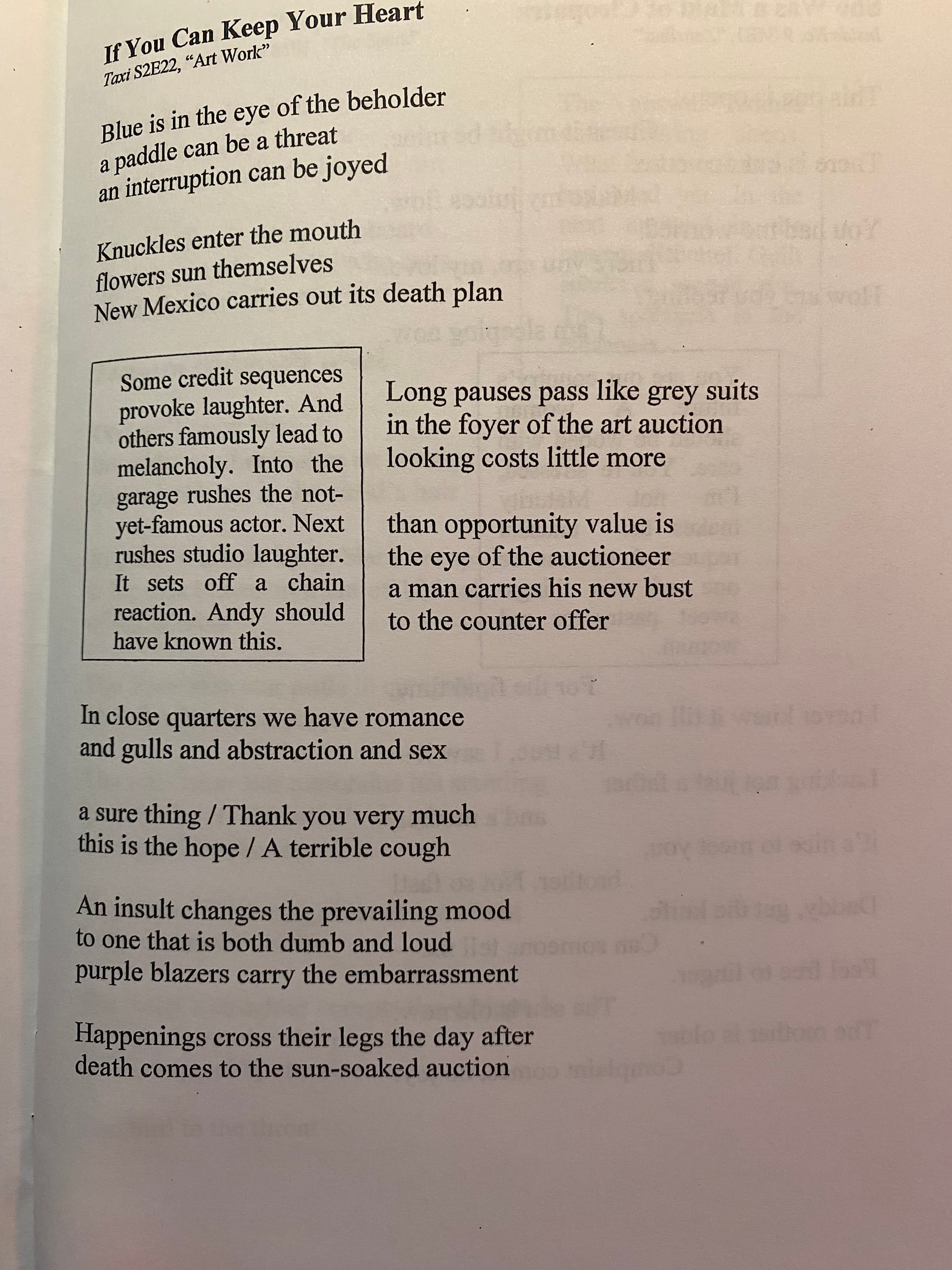

The first poem in Television Poems frames an episode of Taxi. I'm a big fan of Judd Hirsch personally (a big fan of Numb3rs actually), but I never watched Taxi—lots of big names and, more importantly, lots of acclaim. The Wikipedia for it says “widely regarded as one of the greatest television shows of all time” and I’ll have to take the internet’s word for it for the time being because I am an uncultured swine who has literally always never seen that thing you’re talking about. Pretend there’s a salient New Yorker comic between these two paragraphs to illustrate my point about competing listmakers of movies and physical TBRs.

The remarkable thing about MacEachern's poems, however, is that each page has a TV-like window filled with words on every page in the chap:

A lot of full episodes of Taxi are available on YouTube but I am only seeing a clip of Danny DeVito for the episode cited for this poem.

On that inspiring note, this poem is full of bangers:

- flowers sun themselves

- looking costs little more / than opportunity

- Into the garage rushes the not-yet-famous actor. Next rushes studio laughter. It sets off a chain reaction. Andy should have known this.

Magnificent. No notes. Jessi MacEachern knows ball.

But I’m not gonna shy away from writing about poems if they’re based on shows I don’t know, that wouldn’t be right.

The next poem is “She Was a Maid of Cleopatra” based on Inside No. 9’s “Zanzibar” episode. I have quite honestly never heard of this show, either, and it’s been on for the last 10 years.

The whole episode is in iambic pentameter and is directed by David Kerr, who’s also done a dozen and a half or so episodes of Mitchell and Webb.

The poem: all iambs. And I’ve gotta hand it to her, they are as sumptuous as calembours:

- You’re stressed. I’m not.

- Daddy, get the knife.

- I am sleeping now.

I have to go back and re-read it two, three times to bask in it, recite it with an RP accent in my head where the emphasis hits correctly. Stunning. I’ll try not to speak like an Islander now.

The following poem is about the pilot episode of Little Fires Everywhere. This series (I strongly dislike the nomenclature “mini-series,” quite frankly, but it’s eight episodes long) is based on the novel of the same name by Celeste Ng and stars Kerry Washington and Reese Witherspoon. In the first episode of the series, so much happens I feel unqualified to paraphrase. But MacEachern’s poem here is titled “The Words are Purposes” which has a special allure to it, being a poem:

The artist’s daughter twirls

in the lens of the camera

held by her mother’s leaning out

The window is white clapboard

the boy is a white child who asks

about the line of poetry in the air

I came to explore the wreck

One wall turns blue

the white mother makes an attempt

places her hand in the child’s hair

Repulsion is hair burnt black compulsion

is the exact measurement of 125 ml

of white wine

The television star pulls in sympathy

he is the favoured parent

The television star maintains his standing

in white briefs the artist’s daughter

is stopped by the size of it

The house it is a magnificent testament

to generational wealth

The artist’s daughter accepts the whipped

potatoes from the older brother

she is stopped by the size

The bird in the throat

Then, in the box in the upper right-hand corner of the page:

The answer comes

with blaring sirens.

What is shown has not

happened yet. In the

next moment is the

present disbelief. Guilt

sparks a second riot.

The spectacle is the

closeness.

Little Fires Everywhere has all the complexity of an ancient myth but is set in 90s Ohio.

The thing MacEachern gets about ekphrasis and TV is that these poems work like Easter eggs: if you’ve seen it, know it, and then read the corresponding poem, it can be a portal of discovery. A sweet treat. Some poems I can only appreciate at the level of craft because I employed the same technique for 90s PC games for my 2023 chapbook Virtual Lands: MS-DOS Series, with a slightly different execution, but the intents overlap enough for me to get where she’s coming from as a writer.

Do they not have a similar effect, though, if you haven’t seen the series? I can’t make good on my word in the midst of writing this review (in media media res) by copping out saying, “I’ll totally watch it now!” but does it not make you want to see it now that you get this extra layer? Read the novel, watch the series, read the poem: you are now a completely different person. It’s not necessary, we owe the poem nothing, but the possibility lingers. What else is on? Don't flip the channel.

The remainder of the chap (spoiler alert) delves into the following series for a trove of poetic souffle: Sex and the City, The Leftovers, Lovecraft Country, Call My Agent, ER, Mad Men, Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Gilmore Girls, The Get Down, Transparent, Buffy, Parks and Rec, Roseanne, Dawson’s Creek, Breaking Bad, Dickinson, Simpsons, Deep Space Nine, Better Things, Bob’s Burgers, Ramy, Fargo, Avatar, and finally West Wing.

So, take a show I’m most familiar with and dissect it, shall we? I choose The Simpsons, naturally (she actually has 2 Simpsons poems in this chap). I grew up with them, in an era where most kids’ parents wouldn’t let them watch grown-up shows like that. I never saw the issue. I remember once getting judged by my parents for sneaking into the basement to watch an episode of Barney & Friends in 1999 (never again); and I get it. Compared to peak Simpsons, Barney was not good brain food. It's like Robin Williams said in Doubtfire: don't play down to kids, just play to them. It’s like the 90s TV equivalent of that scene in Ratatouille where Remy teaches Émile about taste. And MacEachern, for all my faults, undeniably has it.

Towards the end of her book, MacEachern writes a Simpsons poem for the episode “Behind the Laughter,” a VH1 parody episode.

How can I not share it? I’ve already printed two of MacEachern’s poems above. I can only resist the urge by writing my thoughts: this is the perfect fan service poem, it incorporates lore while depicting a non-canon episode, while also making room for the dénouement of the episode taking place at hand, and pays homage by way of relying on classic Simpsons tropes like casually dropping crossword-like words mid-dialogue: Gates were closed to the father. / That night, fate wore a cummerbund.

Literally a word I heard Bill Hader use in a clip this morning I saw on Instagram, describing his younger self as looking like Charles Manson. Which then leads MacEachern to what I consider the pinnacle of the poem: Gin, evergreen cash, piles of loose caviar. It perfectly encapsulates the episode and the series all at once. I exhale deeply before concluding my review. I have to.

You may remember me from such poems as...

Take a Penny, Leave a Penny

The father is weeping

while the son receives a shoulder massage,

a manicure, a foot rub and says yes.

Learn the secrets

of rising and falling.

Swing then rock, rock then swing,

dissolves into musical argument.

The dream was over.

The town in Somewhere, USA

was put on hiatus. As a young female artist,

begins the young woman. She is

cut off by the television,

always the parental figure. Was the dream

really over? It was.

Gates were closed to the father.

That night, fate wore a cummerbund.

Backs were turned. But is it

really over? It is. The red braids lift.

Will things stay the same? Gin,

evergreen cash, piles of loose caviar.

The clown is not the father

but he is embittered and old.

Behind the streamers, the family rises

and falls. The clouds,

the opening shot,

Somewhere, USA.

Then, in the bottom right-hand corner of the page:

We are overly familiar

with the wife from the

very beginning. The

daughter has a face

streaked with saliva,

not her own. It’s meta,

the way real life enters

the television script.

Firehouses of respect.

In my ultimate fantasy crossover, my friend Shawn Berman and Jessi MacEachern would do a crazy collab. It would go so hard.

Because, at the end of the day, this chapbook represents a machine that Jessi MacEachern has invented, in the sense that it has a mechanism: pick a show, find poetry literally mentioned in it, and turn that episode into a poem, and don’t forget to add the poem-within-a-poem. Ostensibly infinite in potential.

I was watching Deep Cover the other day and Jeff Goldblum literally quotes Delmore Schwartz, one of my favourite poets of all time, mid-conversation with Laurence Fishburne. I totally freaked out. So it occurred to me: you could always break the rules and reinvent it, include movies for example, and expand the possibilities, truly without end.

I look forward to reading Cut Side Down. Jessi MacEachern is a gem. In an alternate timeline where Elon Musk didn’t acquire Twitter, this review would have been live tweeted, minute by everloving minute. But if they ever invent time travel, I would gladly go back to 2021 to do so. It was a gorgeous read. Thanks for tuning in.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.