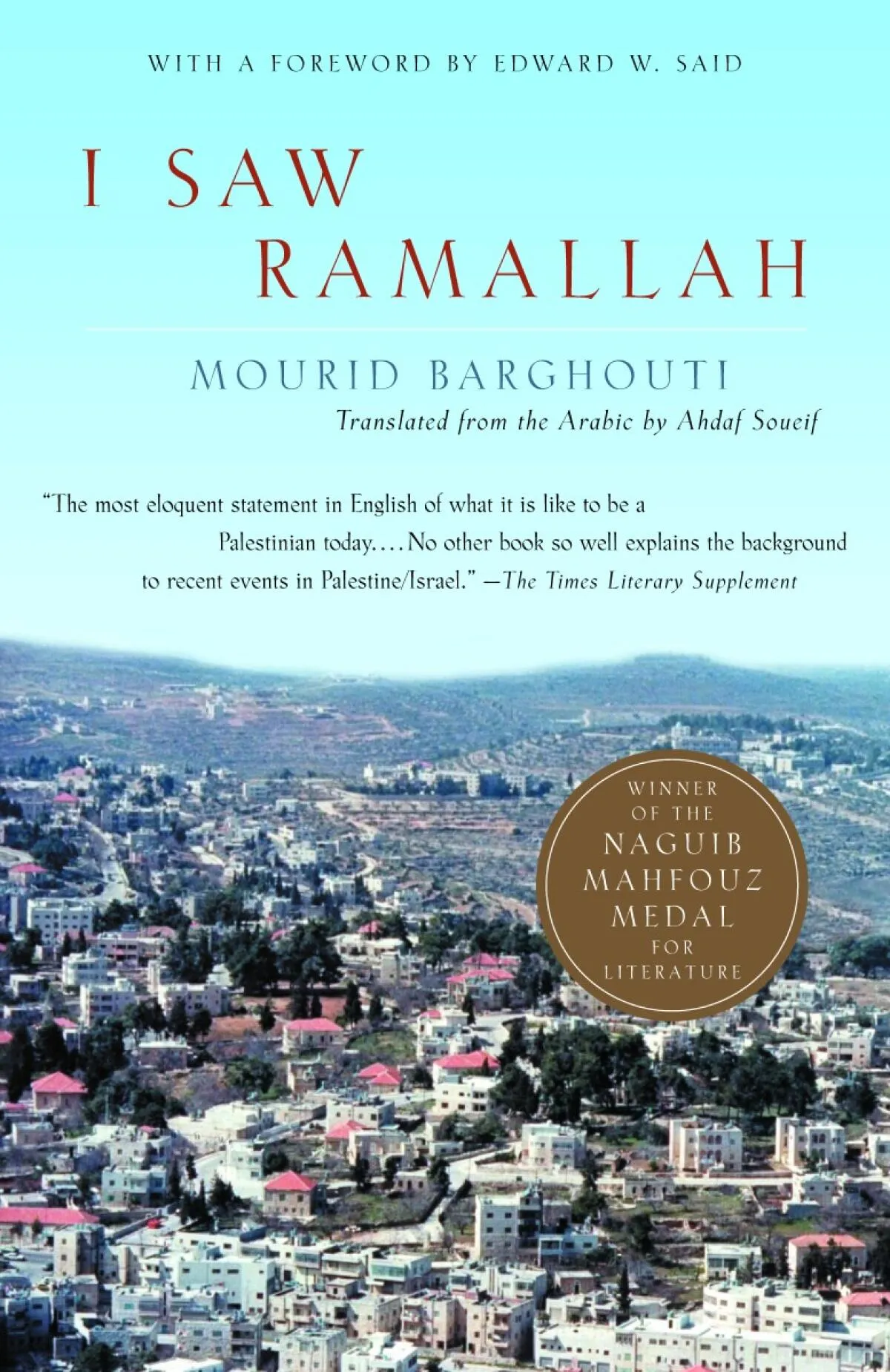

Jerome Ramcharitar, The Riddle of Three Crimson Doors

Jerome Ramcharitar’s first full-length collection touches on a familiar nerve with static electrically charged bliss.

bio

Jerome Ramcharitar teaches English as a second language, has a master's in English lit from McGill, and lives in Montreal. The Riddle of Three Crimson Doors is his second book of poetry, and his first full-length, launches Saturday, June 7 with Cactus Press at Leigh Kotsilidis’s Rocket Science Room. His debut chap, The Wrong Poem and Others Like It, was published by Cactus in 2021.

one-liner

Jerome Ramcharitar’s first full-length collection touches on a familiar nerve with static electrically charged bliss.

quick points

- quizzical, riddling

- self-aware

- romantic and contemporary

- personal and contemplative

synopsis

The Riddle of Three Crimson Doors is a sphinx of a book. At times addressing the reader directly, yet at others waxing philosophically, we are invited by the speaker of the poem to ruminate on life in a deeper train of thought. The reader is cajoled with a reference to Let’s Make a Deal, the famous gameshow by which game theory is often demonstrated, but quickly reminded that although the author is self-aware, it is you who has complete control over this journey. What follows next is a meandering through peaks and valleys of narration, declaration, quasi-apocalyptic visions, Zoroastrian-like eschatology, matriarchal mythology, and bouts of repetition that sound as though they border on the ritualistic or shamanistic rather than merely the lyrical metric of the poems, although prosody lends itself to some free word association play reminiscent of spoken word poetry with undertones of conscious rap.

exploration

Jerome Ramcharitar’s poetry is what good editors are looking for in this country right now, but not enough people have heard of Cactus Press Poetry yet. This, of course, limns their venture with unfathomable potential. Permit me to elaborate.

As much as I am always obtaining and reading new books, I have found in recent years that I always seem to be revisiting things without fail. One of the books I’ve been rereading lately is the sequel to Stuart Ross’s Confessions of a Small Press Racketeer (2005), Further Confessions of a Small Press Racketeer (2015), undeniably the deeper of the two sets of confessions. It just so happens to be ten years since Further came out. It’s 2025, what if Stuart Ross went further again?

In Further Confessions, Stuart Ross mentions a lot of the presses which rose up through the ranks of independent publishing over the years to become stalwart cultural touchstones of the Canadian publishing racket have done away with their commitment to experimentalism.

Not only that, but the vast bulk of poetry manuscripts being accepted for print are largely singular in scope, exploring one theme or subject across roughly 100 pages, as though every full-length poetry book had to serve a dual purpose as both poems and thesis statement. It makes things uninteresting, predictable and repetitive, even when the subjects change from title to title, the pattern’s the same. What Canadian poetry needs now is more vibes writing, as in collections with myriads points of interest, not culminating on any grandiose theme, but exploring things on equal footing between poet, editor and reader.

Stuart Ross goes on to say that careerism need not be a dirty word, albeit likely unrelated to the previous criticism, could be combined with it to make the observation that if there were any careerist experimentalist publishers in the Canadian publishing industry, they would likely have a monopoly on the most exciting type of writing Canada has ever been celebrated for (Derek Beaulieu’s no press fits the mould, actually, shoutout Derek Beaulieu).

Not to be reductive and claim experimental or bust. It might not garner any Governor General's awards (or might) or even keep the lights on, but if it reached the right people at the right time, that would mean so much more than the sort of trade paperbacks publishers put out every quarter while taking virtually no risks with anything ever, or as little as possible. As if taking risks wasn't the entire point.

Sure, we as Canadian writers have a knack for short stories. But as far back as the end of the Second World War, we basically invented concrete poetry. More realistically, we made significant contributions and illuminations in the genre on par with and more often than not soaring past those of our American, Russian, and Western European contemporaries. Concrete, visual, and surrealist poetry lent themselves naturally to inspiring not only other forms of poetry, but other forms of prose and even other forms of printing, typesetting, paper making, etc. It’s touched on everything.

DREAM PHONE CALL

A phone call reminds me why

I find myself in this world.

The voice scratches words up and down

a line of static.

I am miles below anything recognizable

hours into unwilling espionage

when the phone rings in monochrome.

"This world was made to be forgotten,"

the voice says in husky blue.

"But someone chooses to remember."

Wood is a conduit to the past;

longing hardens into the oak

of this place: fine stained furnishing,

a beautiful realm to hide oblivion.

I was alone and afraid long enough

that relief is a drug and I cling to it

with ragged strength, my breaths loosening

to a mild wheeze.

In the last scene of the dream,

I am pissing and wondering

if it was my father who phoned me

world to world

to tell me not to forget.

Jerome Ramcharitar’s first full-length collection touches on a familiar nerve with static electrically charged bliss. He’s got the English degree from McGill but doesn’t write like a grad student. He is so present in his work. This is the kind of poetry Cactus excels at publishing. On these terms, it would be hard to think of a better fit for author or press.

What do I mean by all this? I mean to say, if you were to read the first and last poems of Ramcharitar’s collection, you might mistake it for one of those thematic broad stroke type manuscripts that only touches on one subject or topic. Instead, in between, we are ushered through a form-agnostic adventure of constantly shifting but dramatic voices doting on what can be nothing other than the dark side of existence that remains dirgelike throughout. Aesthetic influences resembling or directly engaging with emo, punk, death metal, abstract art, steampunk, fantasy, cartomancy, and beyond.

His allusions to other writers, artists, and historical figures are sparse but not spartan. Avleen K. Mokha, Zdzisław Beksiński, and my favourite dedication of the collection: “for Mitsuno Ochi, now the shadow of death.”

Aspectively, Jerome Ramcharitar’s verses feel like a photo negative of poems by Khalil Gibran or Rabindranath Tagore, dwelling on the very nature of interrogation, destruction, loss and being lost. You can pick up The Prophet for the umpteenth time and derive a sense of spiritual enlightenment on any given page, sure. You might chance upon a copy of Gitanjali by surprise, see the Yeats blurb and Nobel spiel and say, you know what, I am conflicted by spiritual longing, too. But pick up a copy of Jerome Ramcharitar’s Doors and you will feel the way you did looking into the Eye of Sauron for the first time on film. You will see the light and embrace the darkness.

Another way I might phrase it is Jerome Ramcharitar says a lot in what he doesn’t say. He can be playful, he can be on the nose, he can even be explicitly literal talking about death, without ever losing track of the sublime irony of despair.

On that note, I leave the last word to him:

HYENASONG

Flesh has a secret—

a gustatory truth.

Taste is communicative,

a reality reminding us

there is something beneath,

beyond the fivefold.

Gravitas between gum and tooth and tongue

repeats the sacred fragility:

mortality, time—they are the same.

Strength in numbers means weakness

in few,

death bringing grief

more devastating than gangrene.

When we eat, we engorge on memory

and the sense-meaning of loss and love.

There is quickness in our breath,

survival in our grins and gawking.

Laugh if you like

—we certainly do.

For we know,

there is a secret in flesh,

and in each kill and each killed

we give thanks

to have another part of it told.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.