Derek Webster, The Thinker

It is a parade of those things that make life worth living to the post-Enlightenment humanist poet, dalliances and assurances that feel increasingly seldom in the world we live in today at that.

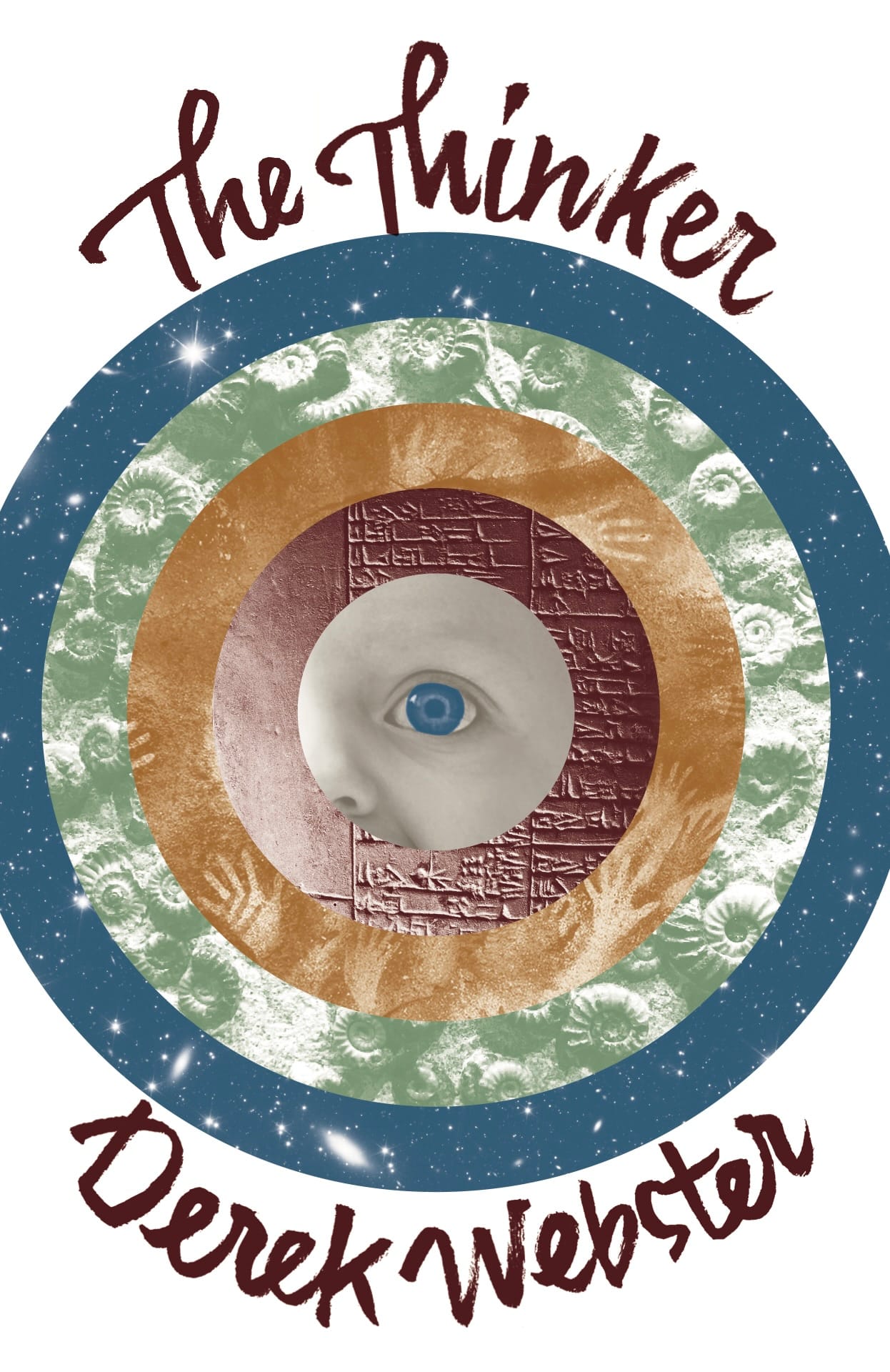

Derek Webster, a name I’ve been encountering with increasing frequency of late, published The Thinker with James Hawes’ Turret House Press in 2024, edited by James Hawes and with an enrapturing cover design by Brian Morgan.

There are a series of concentric rings, with the cosmos on the outermost, then isopod fossils on the next, a very cave-like mosaic of handprints beneath that, then Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics below, and in the centre a big, blue baby eye, matching in saturation and brightness to the outermost cosmic ring. The title of the book and the author’s name appear above and below in curved text respectively.

It is reminiscent of the Nic Cage movie Adaptation, where his character is writing a screenplay and, desperate to start from the start for the sake of narration, decides to start by describing the creation of the universe and everything that’s happened since on a macro-scale that leads to life as we know it now. Beautiful, but not compelling. If anything, an elaborate, expressive form of procrastination. The Big Bang as metaphor for The Big Nothing. The difference with Webster’s poetry being, at face value, the creation myth isn’t evoked for comedic effect.

But you have to hand it to Brian Morgan, it is an impressive pair of artworks, forming a diptych with the back cover: ancient Sanskrit manuscripts encircle the outer ring, with a time-agnostic idyllic market scene underneath, followed by something churchy or Latinate resembling a cartographic sun symbol in front of what appears to be an unlit room being brightened by a large window with the symbol superimposed on top of it, penultimately a field of bodies, perhaps from a genocide or trench warfare photograph, and, finally, a picture of Neil Armstrong’s bootprint on the lunar surface in the middle.

Inside the cover, an epigraph: Brian Greene, American physicist, from his work Until the End of Time. It corroborates, from an astrophysics perspective, the validity and solemnity of the Nicolas Cage scene mentioned above.

Second page, another epigraph: Percy Bysshe Shelley, Hellas, 1822, a poem meant to support the Greek War of Independence.

I’m not an English major, so I’ve only just this year found out that Shelley’s middle name is not disyllabic, to my great astonishment, but I do feel as though I should read more Percy, Wordsworth, and Keats.

My parents were very beholden to Tennyson when I was growing up, and I, at a young age, though fond of Idylls of the King, fell in love with the Greeks by way of Wilde, Byron and Joyce.

Reading the synopsis of Hellas online, I am drawn to the overlap between Shelley’s intent to showcase an ideal civilization in this lyricized version of Athens, and Thomas Mann’s Hans Castorp and his mountainside daydream of Greek society representing a paragon through its elevating of philosophy and culture. You could say it’s a recurring theme across Western literature, of course.

But the point here being that there is an equal Apollonian element of science and knowledge in the Greek equation that could be extended as an allegory for life. And Webster’s choice of excerpt here points to the central idea behind his choice of title: Thought is its cradle and its grave. What its you might ask? This whole / Of suns, and worlds, and men, and beasts, and flowers, [...] ah. Nought is but that it feels itself to be.

So we’re getting into the meaning of life from the beginning of the universe till the end of time here, and what it means to think.

This draws me back to a topic I first brought up reviewing Manahil Bandukwala in 2024, that of epiphenomenology, or that what we experience as thinking beings occurs not independently of the chemical, biological, and physiological realities we inhabit with our bodies, the mind being distinct from it, but attached to it.

I may not be an English major but I know Shelley well enough to know he knew his Greeks.

Suffice it to say, no matter how you cut it, this thing goes deeper, whether you approach it from art or science, body or mind. Let’s get into it, Derek Webster.

Prologue

A few trees at the edge of a depression,

the hills deeply split, a wide gap

we once stepped unbalanced across.

The action

that triggers humans is here. Obsidian

intentions, cached in the canopy, impatient

to part us from ourselves

toward dying.

When homo sapiens unwraps its DNA, we will arrive

like ghosts, conscious of our own non-existence.

Until then, over the valley

silence —

I like that, through this poem, we’ve moved from what I deliberately categorize as heady in poetics to imagery, opening up with this scene of a few trees on the ridge of a gorge, ravine, dell or valley, as it were.

Suffice it to say, this work of poetry has a lot of context to introduce us to before we open and begin reading. Inside, each of the ten poems’ titles are preceded by Roman numeral.

I turn instinctively to the back of the book for hints.

Note

The Thinker takes its inspiration from Wallace Stevens’ The Auroras of Autumn.

[...]

The Thinker attempts to renew what we can share: a contemporary vision of our world in broadly secular, accurate, and humanist terms.

An erasure poem on my part to only include these two sentences, the opener and closer of the note, but I don’t want to spoil the book in case you ever encounter it. This is sufficient context I think to begin my review.

After tracking down Wallace Stevens’ poem and listening to a YouTube lecture about him by Dana Gioia, I finally get where Derek Webster is coming from.

As impressive and John Ashbery- or Frank O’Hara-like as Stevens was, by which I mean inscrutable, not so much like Walt Whitman as the comparison of Harmonium to Leaves of Grass might make you believe, even the opening, eponymous poem to the collection that is The Auroras of Autumn sounds deeply unsecular.

In the video describing Stevens’ life, it is said that he converted to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed. But reading Auroras of Autumn, it is clear this is a man deeply infatuated with the interpretations of scripture and the metatext relating to Abrahamic traditions. There is even hints of Kierkegaard (We were as Danes in Denmark all day long), whose concept of leap of faith was used to explain Stevens’ last minute conversion.

All I’m saying is I spent 5 minutes with this poem and the religiosity on it defies its humanism. Sure, it’s modernist, in the same way as a movie or restaurant review in The New Yorker is modernist for using the odd word or two, such as annealed or paean, to make you hesitate as you reach for the dusty dictionary you never use.

Which is why I am so glad Derek Webster has taken the time to deconstruct the underlying metaphysics of Stevens and apply it in a secular, humanist way to the poems in this chapbook.

There are personal affinities I think anyone could find with Wallace Stevens. For me, I get the job hopping, the appeal of the world of insurance for stability (much like T. S. Eliot had with his bank job, say, or Bukowski working for the USPS all those years), although the turning down of the Norton professorship was disappointing to hear about. And odd words, flourishes of Latin, admixtures of foreign expressions, titles with puns like Le Monocle de Mon Oncle? Fabulous.

But perhaps something is lost on me for not immediately seeing the appeal of a poet who hides himself from his work. We are used to modernists depicting themselves in their work, one way or another, say Proust, Woolf, or William Carlos Williams, even. Stevens may be “the poet’s poet”, but I feel like people who actually enjoy sex, coffee and conversation (to borrow a line from comedian Dylan Moran) read Williams, not Stevens.

Leaving New York City for Hartford, Connecticut was likely what made Wallace Stevens the poet he became; I simply don’t know enough about him at this point, other than his “Emporor of Ice-Cream” poem, to tell whether I morally approve of his having done so.

It doesn’t matter to his life, but it’s a defense I repeatedly have to tell myself to let down when approaching an author’s work for the first time. Eliot’s Catholicness doesn’t offend me, but it doesn’t intrigue me, either. Murder in the Cathedral is more a bore than Milton’s Samson Agonistes. I like Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, though.

Something about Stevens earning 10 times more than the average American during the Great Depression smacks of silver spoon. It imbues his every word with a Borgesian hue. Borges very much appreciated Pablo Neruda’s emulation of Whitman in Canto General; at first glance, one might say Stevens was emulating Whitman in a suit rather than in Spanish.

I enjoy the poems of Carl Sandburg and Delmore Schwartz. These were men who really put their collar, blue and white, into their words, as much as they put themselves into their books, in my opinion.

Without further ado, back to Derek Webster.

The first poem, then, I. Singularity/Genesis.

I’m feeling relieved already.

It’s lyrical, it’s imagist, it’s complex. Humbler, than Stevens, too. I like the way the rhyme drives home the point of these three lines:

Long before our dusty dog of a world

trotted down steps under a cherry tree.

Three lemons, the vaunted singularity.

What does the cherry tree and three lemons represent? It’s probably obvious but I won’t dwell on it, it only makes me think of daiquiris.

II. Entropy/Language follows. This I can get behind, philosophically. In undergrad for linguistics, I was constantly drawn to the essays, lectures and scansion work of Roman Jakobson, who, in a collection of white papers from a symposium, once wrote: whether language forms thought or thought forms expression, perhaps it is the same problem as the famous double slit experiment of quantum physics, where observation alone cannot adequately encapsulate the phenomenon. Language as heat death therefore very much has a Jakobsonian ring to it in my ears.

By the first line, I am hooked by the half-rhyme: Egg-like, the sun delivers ancient light. A few lines down feels like a deliberate impression of Wallace Stevens:

Australopithecus afarensis hop-walks by,

carrying its peaceful, long-limbed name.

Already, by the second poem of the sequence in, Webster has expanded the scope of his meditation. We’re getting into deep sea stuff, genuses and meteorology.

Randomly, I’m reminded that Stevens was mentored by Santayana. I don’t want to be so bold as to posit that his influence carries through all the way to Webster’s verse, but it certainly lingers against the curtains backstage of my frontal lobe. Mentored is likely too confident a turn of phrase. He studied under him briefly at Harvard.

In V. Objects/Distance, another Stevensian echo:

Nothing has changed, you say, swinging round,

forever undestroyed and destroying. Yet,

to break that embrace, the energy required.

Whereas “destroy” in Stevens appears in Auroras here:

This is nothing until in a single man contained,

Nothing until this named thing nameless is

And is destroyed. He opens the door of his house

On flames. The scholar of one candle sees

An Arctic effulgence flaring on the frame

Of everything he is. And he feels afraid.

Webster has maintained much of what makes Wallace Stevens characteristic to readers now. The impersonalness, the lack of poetic I, the syntax, the imagery, the arcanity.

It gives me pause for thought. I happen to recall a number of years ago a Canadian poet, published through either Wolsak & Wynn or PQ, who was doing a multi-book sequence of sonnets, epic poetry stuff.

I’ll look it up and reveal who it was in a moment (The Exile’s Papers: Part Three, Wayne Clifford) because right now it doesn’t matter who. I remember the impression it left on me as a young reviewer, asking myself over a matter of weeks whether I, as a young reviewer, would have the chops to make good on asking for it. After much self-reflection and self-doubt, I demurred. I was very much dabbling in flarf then and thought the assail at demoded forms of verse self-defeating. Now that I am barely much older, though it was half my lifetime ago, I think I made the right decision, and would make the same decision again. Some books are more a challenge to review than would sound genuine. I always read the books I review, and usually read as many secondary sources as possible before drafting, but if I can’t get behind the underlying premise of a work, I won’t feign ever having received it, because my two cents is not worth it if I can’t invest philosophically in the work. It’s hard to write good reviews, but it’s impossible for me to write bad reviews. I can’t stand it.

But that is definitely a part of me I try to keep out of my reviews, not wholly dissimilar to the way Wallace Stevens tries to keep himself out of his poems. It’s an insurance thing more than, I think, it is a white-anglo-saxon-Protestant thing, speaking from both camps personally. For one thing, Stevens was Roman Catholic. Not very demure, Mr. Vice President.

By now I should have thoroughly thrown anyone interested in Webster’s work off the scent with my autobiographical yap to return. I have always felt I put too much of myself into my work.

I am nearing the end of the poems. I am on poem number eight. I must come back here after I’ve read more Wallace Stevens. There is so much going on, so much subdued, so many pleats and folds of intertextual immersion and reply.

Something about the final line of this eighth poem brandishes staying force: Don’t ask what the wet matchbox told her.

Poem nine. Burbler: one who burbles. Burble: a gush of rapid speech, or the turbulent boundary layer about a moving streamlined body.

I think scientists have managed to freeze a photon recently. This poem reminds me of that. Phlogistonical metaphors. We are dealing in the outdated, the futuristic, the paths less travelled before they were less travelled again.

The last poem of the sequence is a nod to Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide which I admire. In a way, you could say Douglas Adams is a concentrated form of Wallace Stevens injected into a sci-fi alternate reality to become coherent, like freezing a photon. That’s what this poem makes me reflect.

We’d already left, our foresight a kind of ark,

pushed grapheme needles above the clutching air

to carry us to barges floating in space,

a great success to match our greatest shame,

terraforming another world to suit our needs,

subverting its own cold flowering.

This is unadulterated Derek Webster, stripped of influence. It all comes together, all comes into focus, right near the end. The irony, the comedy, the cosmogony of allusion converges into a pointillist poetics entirely his own.

How did I miss this before? I turn the page to re-read the note. On the page opposite, his bio: Derek Webster is the founder of Maisonneuve magazine.

The blurb on the back by Diane Seuss describes this work as “an epic, physics-driven creation myth” written “without a modicum of sentimentality.” I don’t see how that’s supposed to be a good thing, but it’s intended as praise for his ability to distill his inner Wallace Stevens. I think it’s a success, even though I fundamentally disagree with Seuss. This is a deeply sympathetic work, the desire to set the record straight for the sake of the observable universe and those of us who dwell herein.

The language is not as uninviting as Wallace Stevens and is much more digestible. This is not intended as an affront and as a reviewer, it makes me somewhat glad, if somewhat undaunted, to not have to look up so many Latin words for a single poem.

If you want a physics-driven creation myth, by all means, Asimov or José Martí. “Unsentimental” is not so much mischaracterizing Derek Webster’s work as overstating it, that’s not what he’s doing here, in my eyes. Read any Asimov and you will see how much more sentimental than artists’ the triumphs and tragedies of physicists and chemists can be.

What Derek Webster has accomplished here, I would venture as far to say, is an assertion, say Hans Castorp in a Proustian fever with a Marianne Moore-ish edge.

That’s too many qualifiers to count for anything. Let me recapitulate.

Derek Webster’s The Thinker is a deliberately whimsical, but serious, laying out of one’s cards. This is a worldview, as in this is one way to accept things as they are, but this is what’s important to acknowledge, and the poetry of it all is how fleeting and variegated and random and beautiful living life with a Lucretian edge really is.

It is a parade of those things that make life worth living to the post-Enlightenment humanist poet, dalliances and assurances that feel increasingly seldom in the world we live in today at that.

In summation, I thank Derek Webster for formally introducing me to Wallace Stevens for the sake of this review. I look forward to reading his and your other works soon.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.