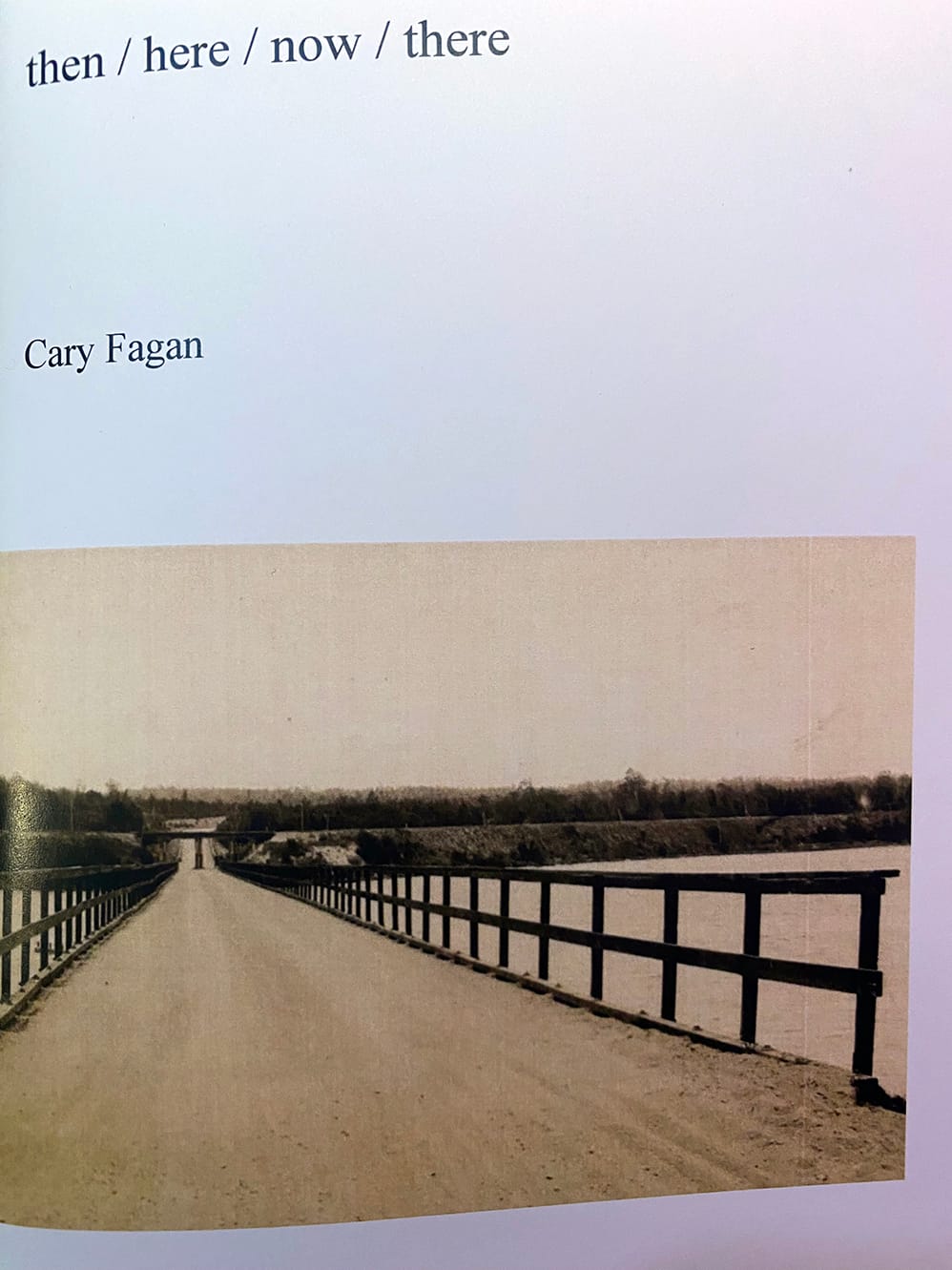

Cary Fagan, then / here / now / there

He makes it look effortless, but these poems are elastic balls of references, stories and allusions begging to be unraveled.

I have to steal this guy’s idea for a blog.

I don’t know how I’m only finding out about this now, but I am sat here this evening with Fagan’s 2025 above/ground chap then / here / now / there and reading his bio in the back to get a foot in the door to begin this draft and I wish I had stumbled upon this in my piles of books sooner.

Now I have to go read every review he’s written.

The words then and there are deictic opposites from now and here, a qualifier I don’t often have occasion to toss into casual conversation. There’s probably a pretty good XKCD chart floating around out there to illustrate my point.

But parlour yap isn’t the point of my writing tonight. I want to take a good look at this object in front of me, which has a sepia-like photograph on the cover of a dirt road banked up over a stretch of water running perpendicular to the viewer, with wooden railings on either side and a T-bone bridge structure at the vanishing point. It’s a very cozy picture that perfectly illustrates place and time by way of metaphor of a foot journey.

Opening the work, a cryptic message epigraphs the page opposite the first poem: various kinds of sake, it reads.

Let’s not get discountenanced so soon. It’s a curve ball, granted, but we’re in this reading together. We’re gonna make it.

The first poem has no title, which I am fond of (besides, titles are hard, as are opening lines, closing lines, and the stuff in between, in that order):

a man on tenth street planting begonias / how afraid

and yet desperate to get up before class / she’s trying

to learn harmonica / torn / you say to him, ’you are my

torturer’ / last night dreaming that i was dreaming of

my father / it isn’t necessary to finish war and peace,

is it? / when I have a good pen i want to write for its

sake

So many things happening here:

- we are introduced to Cary Fagan’s style in this poem

- the preference is for lowercase letters where possible

- we have one capital I in the last line of the poem

- the poet doesn’t mind having single-word lines in a poem

- the poet doesn’t mind italics, which are multi-functional

- but no periods, colons, semi-colons, or dashes

- only slashes, commas, apostrophes, and a question mark

- the last word bringing up the epigraph again, sake

It will be a small miracle if I don’t have to photograph the poem to get the typesetting to appear in its correct format from the book to the screen (Update: didn’t have to (on desktop)!).

All that being said, I think we have established sufficient ground rules to proceed on this mission together. What do his poems have to say?

Let’s circle back to this poem once we’ve looked at the next one the next page over:

sweetener / the marionette cellist dressed identically

to the man above / dink car left in a stocking by my

angry mother / yo, you have to be naked / getting the

4, 5, or 6 from astor place / i listen to solange because

sophie asked me / am i the only one who wants to be

thought of as nicer than i am? / the various kinds of

sake in the hiromi kawakami novel

So here we are once again woven sporadically through a biography that is in the process of being revealed to us through the slits of the blinds, one index finger peek at a time.

We are now immune to most orthographic devices because of the bulleted list we extracted from reading the first poem.

We are surprised, however, by the homograph plot twist of ‘sake’ being turned into a disyllabic loan word from the Japanese rather than the, I wanna say Norse Germanic, monosyllabic ‘sake’ we had assumed for the first two pages of the work.

We are provided more clues: astor place, a minuscule slice of New York; solange, the singer, no doubt; hiromi kawakami, a Japanese writer.

Now that we have encountered the two most obvious interpretations of the grapheme ‘sake’, I wonder what other various ‘sakes’ we’ll run into in the poems to follow.

Something about this chapbook, having been written by someone who occasionally reviews chapbooks, makes it feel like a treasure hunt. There’s a thrill to it. What we may discover.

In the least conventional line breaking manner, with as few safety railings against misinterpretation as possible, it does feel once again, to borrow the computer science phrase as I did the other day, like these poems operate pretty close to the metal (of the poetry machine).

This section ends, giving way to the next section, dutch novels. I realize now what I mistook for an epigraph is in fact a section header. It appears on the back of the page, or the left when the chap is spreadeagle, in all lower case letters, of course.

When I think of Dutch novels I can only conjure two to wit: In the Dutch Mountains, Cees Nooteboom, and Strike Out Where Not Applicable, Nicolas Freeling, the former being a Dutch writer of considerable repute and the latter being a novel set in the Netherlands and billed in the précis as “the thinking man’s Ian Fleming.” It’s all right so far, I just started it the other day. Sometimes no idea where the books I have come from to be quite frank.

Remembering the tangent I was on, I realize Fagan has stayed true to the title of his work: then takes place in these poems in the first two-three lines; here follows next, place taking priority over time; now is the natural segue from current physical location to current temporal; and there very much leads us astray, but not a red herring—it’s exactly as printed on the tin.

Taking it all in with a sharp inhale makes reading the following poem so much more relieving:

cars sluice through the college street rain / a cat

whose need is never sated / curve of the blade to make

the spoon’s bowl / tic tacs i carried around as a boy

like cigarettes / the splintered end of a season /

listening to allison de groot’s banjo / the air, the air

We can finally rest easy taking in the imagery, the metaphor, the combination thereof, the nostalgia, the unexplained use of italics, and the music tie-in, with a melodic enough coda to say Cary Fagan has tied it all off with a neat little bow.

The last poem of the section asks rhetorically at one point “why are there so many writers” and may or may not be a stray piece of unanswered dialogue.

There are two more sections proceeding, keeping true to the implied structure of the book. They are “any moment now” and “waiting by my father” and suddenly everything in this chap feels too brief. I want more. It’s not even over yet and I feel the impending, undesired burden of the abrupt end to come.

The other thing I notice about these words that may not appear explicitly to every reader is how prone this poetry would be to translation. There’s nothing ambiguous, despite the lack of orthodox structure; the poems aren’t long nor long-winded. Each page is one stanza, six lines apiece, and the last line sometimes only one word. It is perhaps a privilege of having been translated so frequently that Cary Fagan can write this way, he’s already familiar with the life and longevity of any given work.

As far as reviews go, I am no Colm Tóibín, although I truly wish I were. He would know exactly which bits to go after without giving an exegesis of every line in the work, even though he probably could. I am getting distracted again, aren’t I?

Something about reading Cary Fagan’s chapbook weakens my resolve to stay on topic. I want to gush about my own favourite writers, musicians, memories and anecdotes, too, although that may mischaracterize the nuanced tone of each poem here. There are wisps of pain, of lucidity, of dubious regret, and quiet delight. It’s all rolled into one, but as brief and nebulous as the poems are, it’s clear when you read which is what.

So, it’s rather impressive, in that light, how succinct and barebones Cary Fagan was able to make this book. He makes it look effortless, but these poems are elastic balls of references, stories and allusions begging to be unraveled.

On a closing note, in the process of formatting and fact-checking this review, I have just discovered Cary Fagan also publishes chapbooks, under the name Found Object Press. Now, I can’t wait to read those, too.

Bibelotages Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.